At Their Fingertips: WCT’s New Wildlife Crime App For Foresters

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 2,

February 2022

By Purva Variyar

The fight against wildlife crime is an uphill battle. Law enforcement authorities are often overwhelmed as they cope with the growing scale and ever-changing modus operandi of wildlife criminals. Wildlife crime is now one of the most profitable organised crimes in the world, preceded only by the trafficking of arms, drugs, and humans. The knock-on effects of hunting, trading, and over-exploitation of species to meet the burgeoning demand worldwide are as devastating for wildlife populations and ecosystems as they are for rural livelihoods and economies.

While in theory, India’s legislation boasts of some of the most robust and stringent wildlife protection laws and provisions – the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, Forest Conservation Act, 1980, the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, and Biological Diversity Act, 2002 – in practice, the subpar state of wildlife crime investigations and convictions present a stark contrast. In India, less than five per cent of wildlife cases result in rightful criminal conviction. The cases that do see conviction of wildlife offenders often translate into a disproportionately light judicial punishment. This sets a precedent of undermining the seriousness of wildlife crimes, and fails to deter poachers and traders.

Kiran Rahalkar (in blue) conducting a site security training module for frontline forest staff in the Pench Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, as part of WCT’s Wildlife Law Enforcement Training (WLET) Programme. Photo: WCT.

The Anatomy Of Wildlife Crime Investigations

The legal journey of a case involving wildlife crime – until the passing of the judgement – entails initiating an investigation, proper handling and processing of evidence and the crime scene, levying appropriate charges against the accused, gathering robust intelligence, and establishing strong witnesses, by the law enforcement authorities such as the state forest departments. The quality of investigation, evidence, and case will ultimately determine the sentence prescribed by the judge. The weaker the investigation, the weaker the case, and thereby, weaker is the judgement passed. Getting off easy further instils confidence and motivation among the perpetrators to commit more wildlife crimes, in turn overburdening the already understaffed and overworked forest workforce, and ultimately affects their ability to perform investigations. This is a vicious feedback loop that has been set in motion by an apathetic system that is doing little to build the capacity of the foresters who are deprived of funding, training and necessary support.

The Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) has been systematically working towards addressing major gaps that exist within India’s forest protection mechanism. One such glaring lacuna is the lack of training and capacity-building of forest staff with respect to law enforcement, wildlife crime investigation and jurisprudence.

“WCT has engaged in law enforcement training for nearly a decade now, and we have trained over 14,000 frontline forest staff across nine states in India,” says Kiran Rahalkar, who heads WCT’s Wildlife Law Enforcement Training (WLET) Programme.

WCT established the WLET programme with the focused aim of creating better capacity for on-field enforcement responses to wildlife crime. “The programme has been designed to impart effective understanding and skills among forest staff to be able to implement wildlife law, wildlife forensics and crime scene management practices,” Rahalkar adds.

Analysing past court judgements is a crucial step in criminal case proceedings. Studying them helps investigation officers to construct their own cases, replicate the rights, avoid loopholes, backtrack, and connect the dots. Wildlife case judgements are made available on the public domain online, but Rahalkar realised that most of the wildlife cases were rather difficult to access and the databases were ambiguously catalogued. It is essentially “a black box” of judgements, according to Rahalkar. This, in turn, hampered the efforts of forest staff and affected the quality of wildlife investigations in more ways than one.

“It is critical to develop understanding about the crucial lapses that make the cases weak. And for this, a more streamlined access to court judgements on wildlife cases is necessary,” says Rahalkar.

-Edited-2_C-1700_1644218993.jpg)

While in theory, India’s legislation boasts of some of the most robust and stringent wildlife protection laws and provisions, in practice, the subpar state of wildlife crime investigations and convictions present a stark contrast and fail to truly ensure protection of our wildernesses. It is also important to build forest staff capacity to combat wildlife crimes. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria.

An Idea Is Born

When the COVID-19 pandemic brought most activities to a grinding halt, WCT decided to make the most of the imposed lockdown. Forced to press pause on fieldwork temporarily, Rahalkar set himself the ambitious and tedious task of combing through the online database of court judgements from Maharashtra’s district courts, ranging from 1992 to 2015. In the process, he distilled 529 wildlife judgements and meticulously catalogued them based on district, court, species, level of legal protection accorded to the species, nature of crime, charge/s, legal section, and the nature of the final judgement (conviction or acquittal). He teamed up with Pooja Dewoolkar, Economist with WCT, to dissect and analyse each case to understand underlying procedural differences between wildlife cases that have resulted in conviction and acquittal.

Of the 529 wildlife cases, only 19 per cent had concluded with legal convictions of the criminals while in 39 per cent of the cases, witnesses had turned hostile due to various reasons. This is reflective of the larger dismal state and treatment of wildlife cases. With minimal resources and capacity for investigation among the forest staff, and limited understanding of wildlife law among forest staff as well as lawyers and judges, most wildlife cases seem doomed from the start.

“While each judgement has a unique insight to offer on how the Wild Life (Protection) Act has been implemented, when seen together, a few patterns emerge. For example, the section on hunting has been applied in the majority of cases (68 per cent of the 529 curated wildlife judgements), which demands that there should be allied evidence for the case to hold up. In the absence of relevant evidence, the likelihood of acquittal of the accused increases,” explains Dewoolkar. It is important that the right legal sections and terms from the law book are invoked, as doing the opposite proves to be counterintuitive and leads to weak construction of cases.

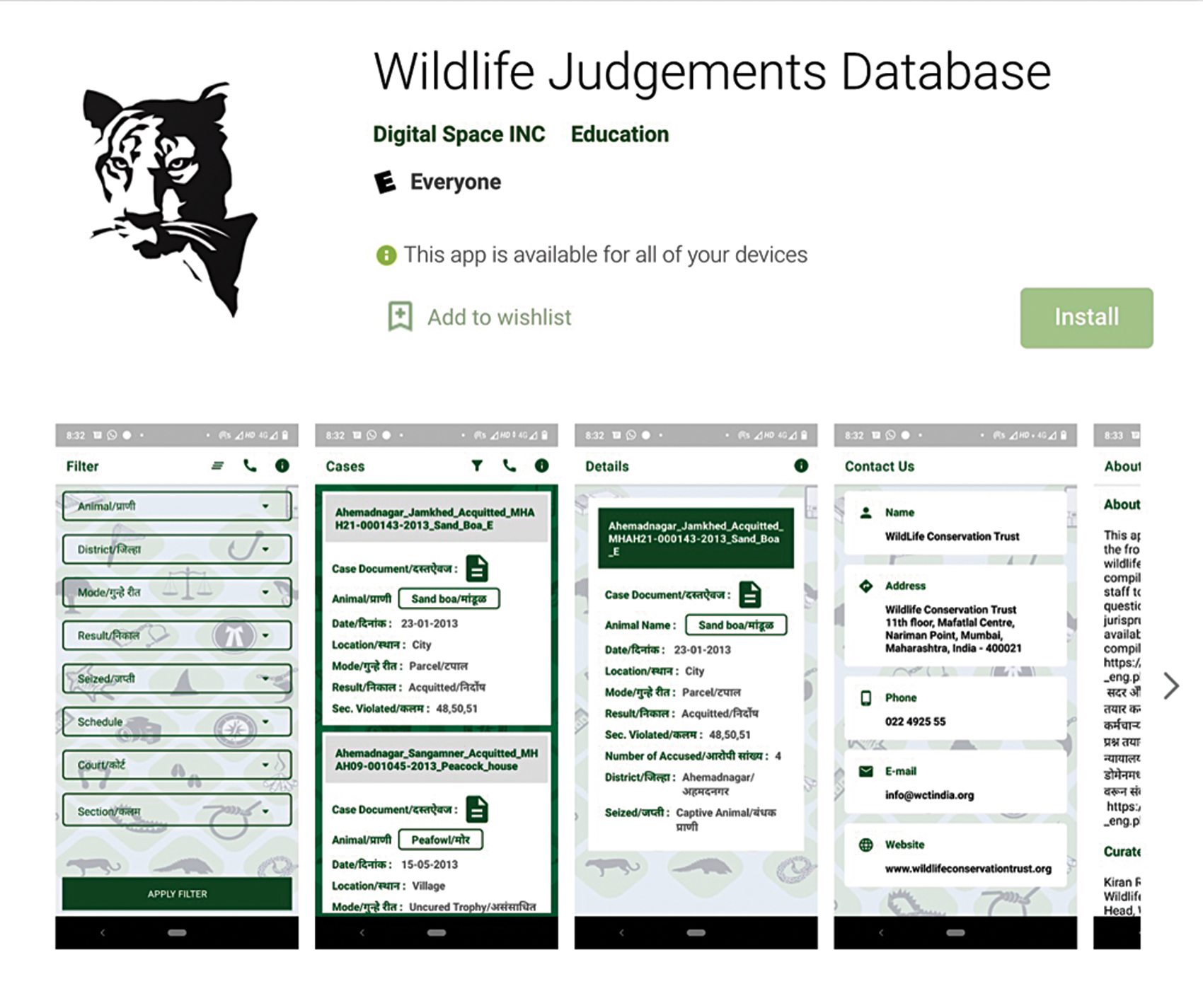

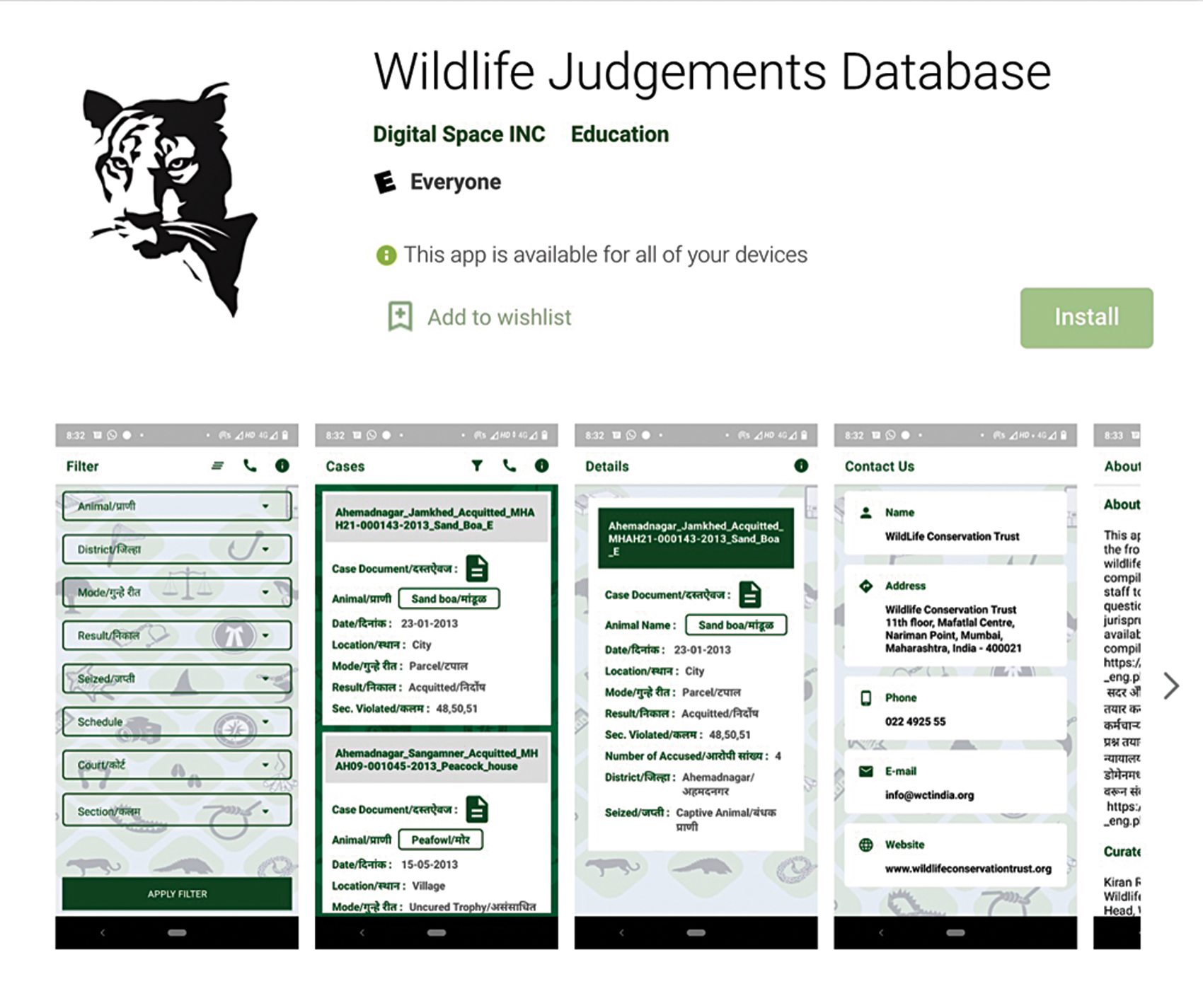

WCT’s ‘Wildlife Judgements Database’ app is available on Google Play Store.

The goal is to make the curated repository of wildlife judgements easily accessible to the forest staff, at the ready, to build strong cases. The ubiquity of smartphones made turning this repository into a mobile application the most logical solution. And thus, WCT’s ‘Wildlife Judgements Database’ application materialised and has been designed keeping the needs of the forest workforce in mind.

“The prime focus of this application is to make accurate information available to the forest staff at their fingertips and empower them to process the cases in an efficient manner, thus saving them precious time and effort,” says Rahalkar.

The Wildlife Judgements Database app is now available on Google Play Store and can be perused in English and Marathi. WCT is working closely with the Forest Department to ensure that forest staff across all districts of Maharashtra are made aware of the app.

However, this application is just the beginning of an ambitious India-wide effort to build an exhaustive application resource of wildlife case judgements that encompass all states, and make it accessible in most regional languages. The dynamic nature of the application allows for updates with newer cases and features. Furthermore, its availability on a widely-used forum such as the Google Play store is intended to benefit not just the forest staff, but researchers, students, government officials and the general public as well.

“The app has been conceptualised to improve access to important judgements for frontline forest staff so that we can target the low wildlife crime conviction rates. Hope this collaborative effort between the Maharashtra Forest Department and WCT enables us to tilt the balance in the favour of wildlife,” says Dr. Anish Andheria, President, WCT.

Purva Variyar is a Conservation and Science Writer with the Wildlife Conservation Trust. She has previously worked with Sanctuary Asia magazine and with the Gerry Martin Project.

-Edited-2_C-1920.jpg)

-Edited-2_C-1700_1644218993.jpg)