COP26

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 12,

December 2021

Text and Photographs

By Shailendra Yashwant

One Step Forward and Many Steps Backwards

The 26th Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC, the COP26, dubbed as the “last, best hope” to cope with the unfolding climate crisis, concluded in Glasgow, United Kingdom, on November 13, 2021, with what many see as one step forward and many steps backwards.

The conference was held after two years, following its cancellation last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. After two long weeks of negotiations, 197 nations agreed on the ‘Glasgow Climate Pact’ that has technically kept alive the hope of capping global warming at 1.50C, the key threshold of safety set out in the 2015 Paris agreement, but disappointed many with its lack of progress or ambition on climate finance and addressing loss and damage from climate change.

The most important achievement of the conference was that the Rulebook for the Paris Agreement of 2015 was agreed upon and finalised. The rulebook will fix the transparency and reporting requirements for all Parties to track progress against their announced emission reduction targets, also known as the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and prevent cheating. The finalisation of the rulebook was absolutely essential to operationalise the Paris Agreement as scheduled this year.

Another small step forward in the Glasgow Climate Pact is the recognition and emphasis on the role of nature and ecosystems, including oceans, in mitigating the effects of the climate crisis. It calls upon countries for “protecting, conserving and restoring nature” – avoiding the contentious phrase “nature-based solutions”. To achieve this, a side deal was struck between 124 countries to end deforestation by 2030. India chose not to be part of this agreement, citing objections to ‘trade’ being included in that agreement’s text.

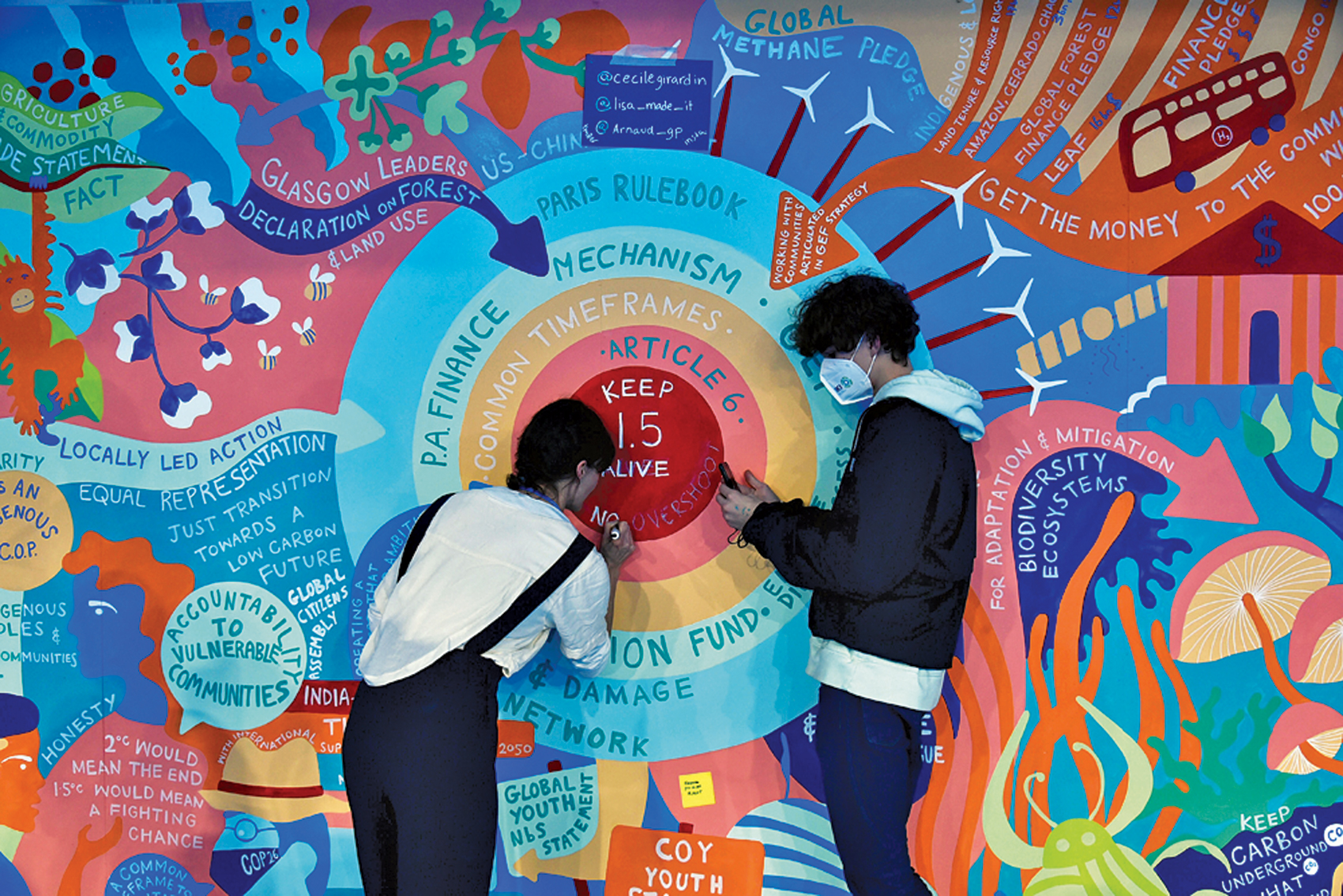

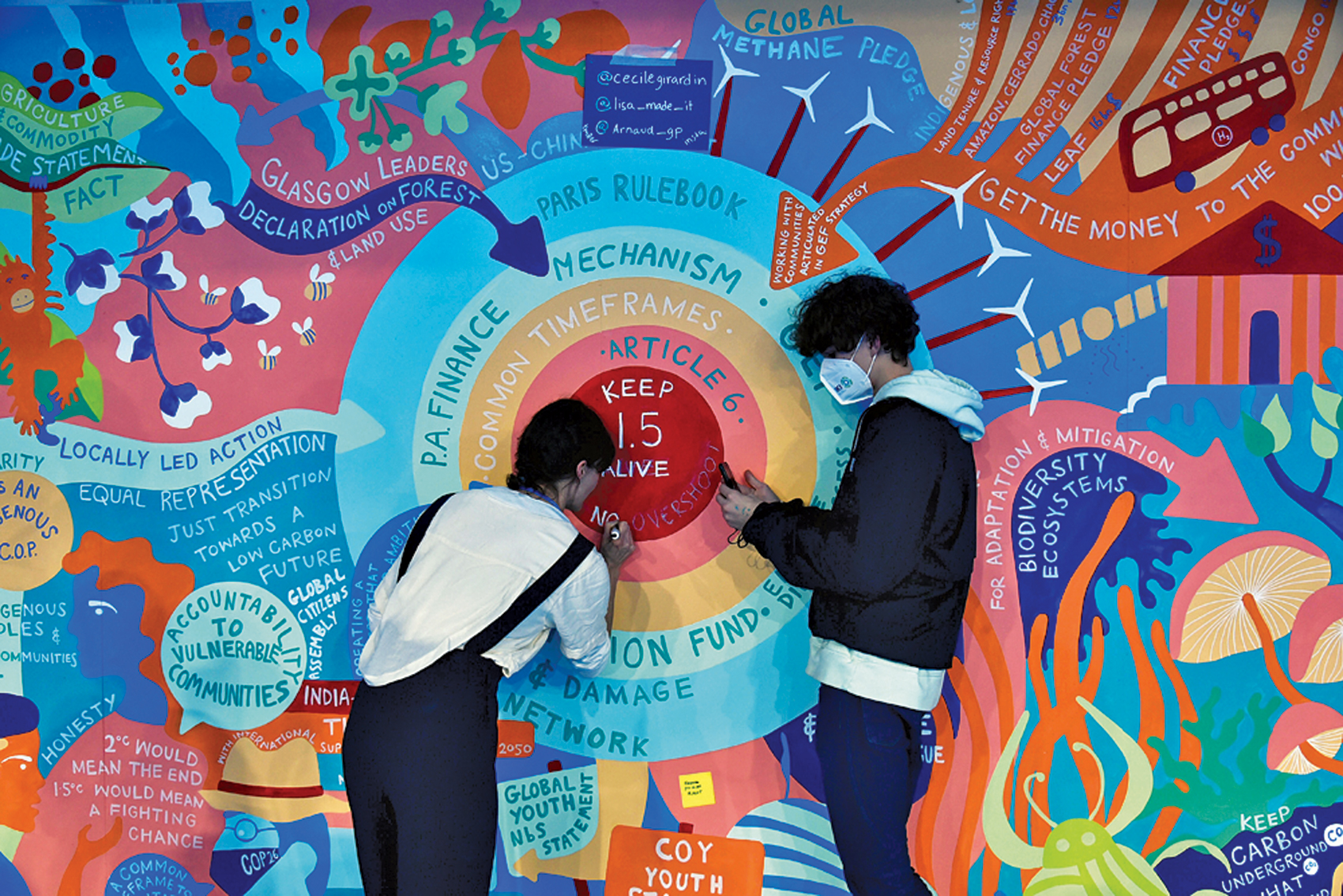

Young attendees express their angst and concern through art at COP26 asking leaders to listen to their solutions and demands for a more just future.

Yet another tiny step forward was the progress on methane emission reduction, after China and the US signed a pact to deal with methane, the second deadliest gas after CO2 responsible for warming of the atmosphere. There is hope that this will help other countries to step up and join the fight to reduce methane emissions in the coming years, with the same level of cooperation as the efforts to reduce CFCs in the atmosphere.

A controversial breakthrough was agreement on the Article 6 of the Paris rulebook to establish a global carbon market and govern bilateral carbon trading, a complex issue that was not agreed on in the previous two summits due to a lack of consensus. This time around, the BRIC bloc – Brazil, Russia, India and China – ensured that the credits registered from 2013 will be allowed to be traded and used by countries towards meeting their climate plans. This one is a dodgy step forward because even as it addresses some big cheating loopholes, it still carries the risk of greenwash and allows countries to shift pollution from one place to another.

This minimal progress has infuriated the delegates from the most vulnerable nations, from civil society organisations, and youth activists from around the world, who were expecting that this COP, unlike the past ones, would set a higher bar for urgent climate action.

1.50C The science is explicit, and the Glasgow Climate Pact requires us to ensure that the world limits warming within 1.5°C in the next decade or so. Scientists have warned that if the world does not set tougher emissions-cutting goals, climate change will unleash multiple catastrophes including (but not limited to) extreme sea level rise, crippling droughts, monstrous storms and wildfires – far worse than those the world is already suffering.

Before COP26, the world was on course for a dangerous 2.70C of global warming. With the new announcements made during the Conference, it is now estimated that we are heading for somewhere between 1.80C and 2.40C of warming, which is still nowhere near sufficient. To attempt to solve this, the Glasgow Climate Pact has asked governments to strengthen their targets by the end of 2022, rather than every five years, as previously required, and put us back on track for 1.50C of warming, maintaining the upper arc of ambition under the Paris Agreement.

The pact states that “limiting global warming to 1.50C requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions.” This means cutting emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 and net zero by 2050, compared to 2010 levels.

In order to deliver this promise, COP26 also agreed for the first time to accelerate efforts towards the ‘phase-down of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, and recognised the need for support towards a just transition.’ This brought initial cheer in the hallways of the SEC, the venue of COP26 and outside it. Remember. fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – the main cause for CO2 emissions and global warming, were never mentioned in the previous 25 COPs, not even in the Paris Agreement.

India’s environment minister Bhupender Yadav came under heavy fire for insisting on changing ‘phase out of coal’ to ‘phase down of coal’. But India has denied this and according to Indian negotiators, the phrases were already in the text introduced by USA and China. Mr. Yadav defended India’s position by stating that: “It was reasonable for developing countries to use fossil fuel subsidies, for example on cooking gas for low-income households. Developing countries have a right to their fair share of the carbon budget.”

CLIMATE FINANCE Climate finance was always identified as the deal breaker for any progress at COP26, especially as the rich countries had failed to deliver on a pledge to mobilise $100 billion a year by 2020 to help countries cut emissions and cope with climate impacts. Under the Glasgow Climate Pact, countries “noted with deep regret” that the finance goal had not been met and agreed to “significantly increase support” for developing countries beyond the $100 billion annual target.

The pact “urges” developed countries to fully deliver on the goal “urgently and through to 2025”, emphasising the importance of transparency in setting how the pledge will be met. It “calls” on developed countries to provide greater clarity on their finance pledges.

On climate finance, the agreed text commits developed countries to double the collective share of adaptation finance within the $100 billion annual target for 2021-2025, and to reach the $100 billion goal as soon as possible. It is important to note that the current goal of $100 billion was to be achieved by 2020. According to OECD, this target will be met only in 2023.

What has changed is now there is more money for adaptation to our new climate reality, if and when it comes. Earlier, 75 per cent of the money went to mitigation and a mere 25 per cent to adaptation funds, the more urgently required fund to help vulnerable countries deal with the ongoing impacts of the climate crisis. Parties also committed to a process to agree on long-term climate finance beyond 2025. Developing countries can now hope for a functioning market in carbon emissions, through which they can raise money to deal with the impacts of climate change.

An estimated 30,000 protesters, mostly children and young people, marched in Glasgow city centre on Friday, November 5, 2021, to call on world leaders and negotiators at the COP26 climate summit to act quickly and effectively on the climate crisis.

LOSS AND DAMAGE A block of most vulnerable countries ‘Climate Vulnerable Forum’ and civil society organisations brought the demand of dedicated funding for loss and damages, to compensate victims of extreme weather events and rising seas.

G77 and China, which represents 134 developing countries, even put forward a proposal for a funding facility dedicated solely to the issue. The contention being, that the most poor nations were suffering the impact of climate change today due to the inability of the rich and developed countries to mitigate their emissions for last three decades and further fuelling the climate crisis.

Unfortunately, this proposal was blocked by the US and EU, who insisted that humanitarian aid can do the job. They did not further discuss any new funding channels.

Instead, they conceded to establish a Glasgow dialogue between parties, stakeholders and relevant organisations “to discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimise and address loss and damage associated with the adverse impacts of climate change.”

“The voices of the most vulnerable and the most impacted by climate change have been silenced, and the interests of the fossil fuel corporations pandered to by the U.K. COP presidency,” said Sanjay Vashist, director of Climate Action Network South Asia, responding to the Glasgow Climate Pact. “Instead of building trust, the global south has been cheated again. Instead of funding for loss and damage, we have yet another greenwash that will ensure genocide by extreme weather events in developing countries.”

Shailendra Yashwant is an independent photographer, writer and journalist. He is currently senior advisor to the Climate Action Network South Asia and steering committee member of the Pesticide Action Network India.