Goldmines Revealed - Field Stories from Indian Golden Gecko Habitats

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 42

No. 2,

February 2022

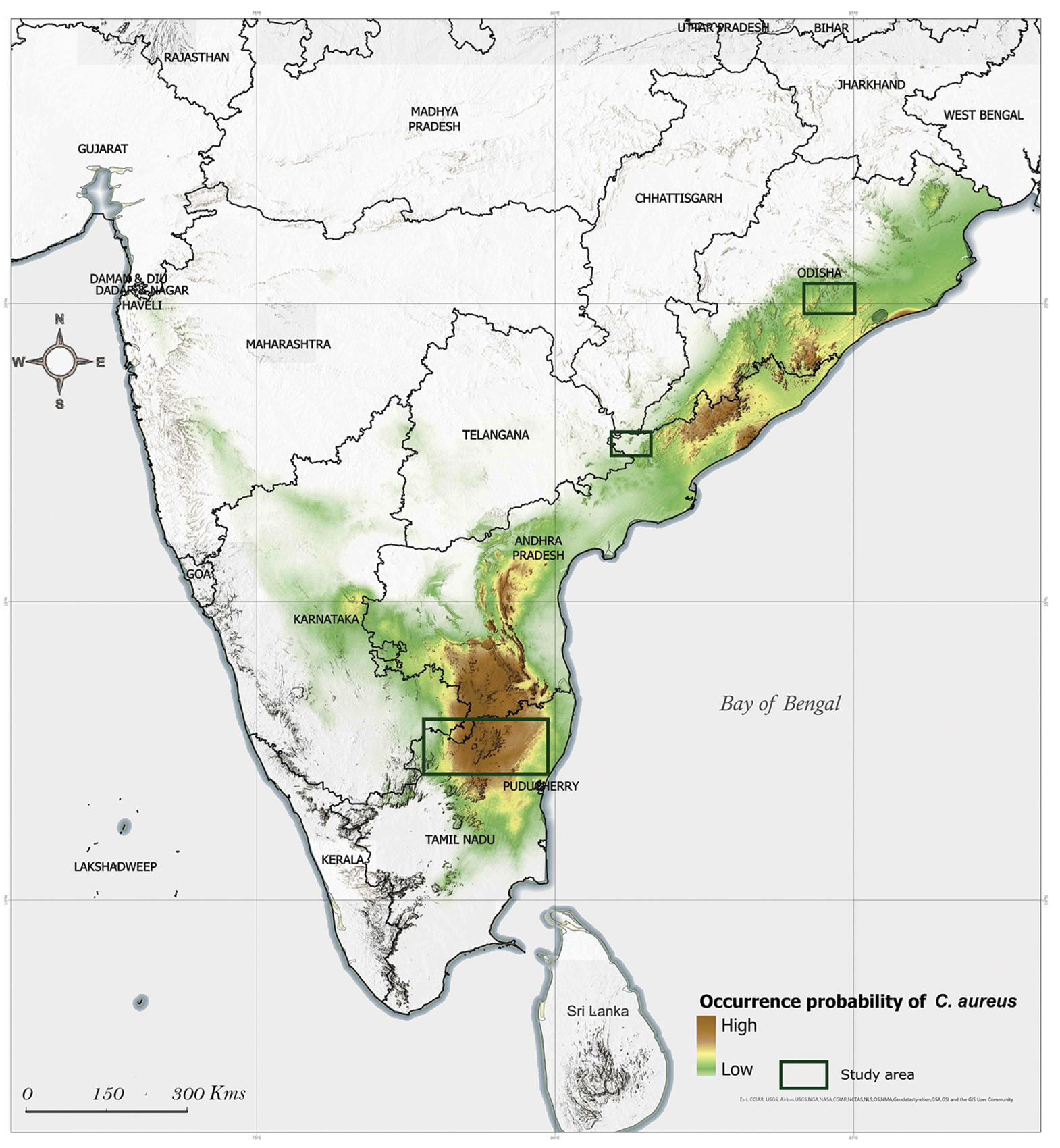

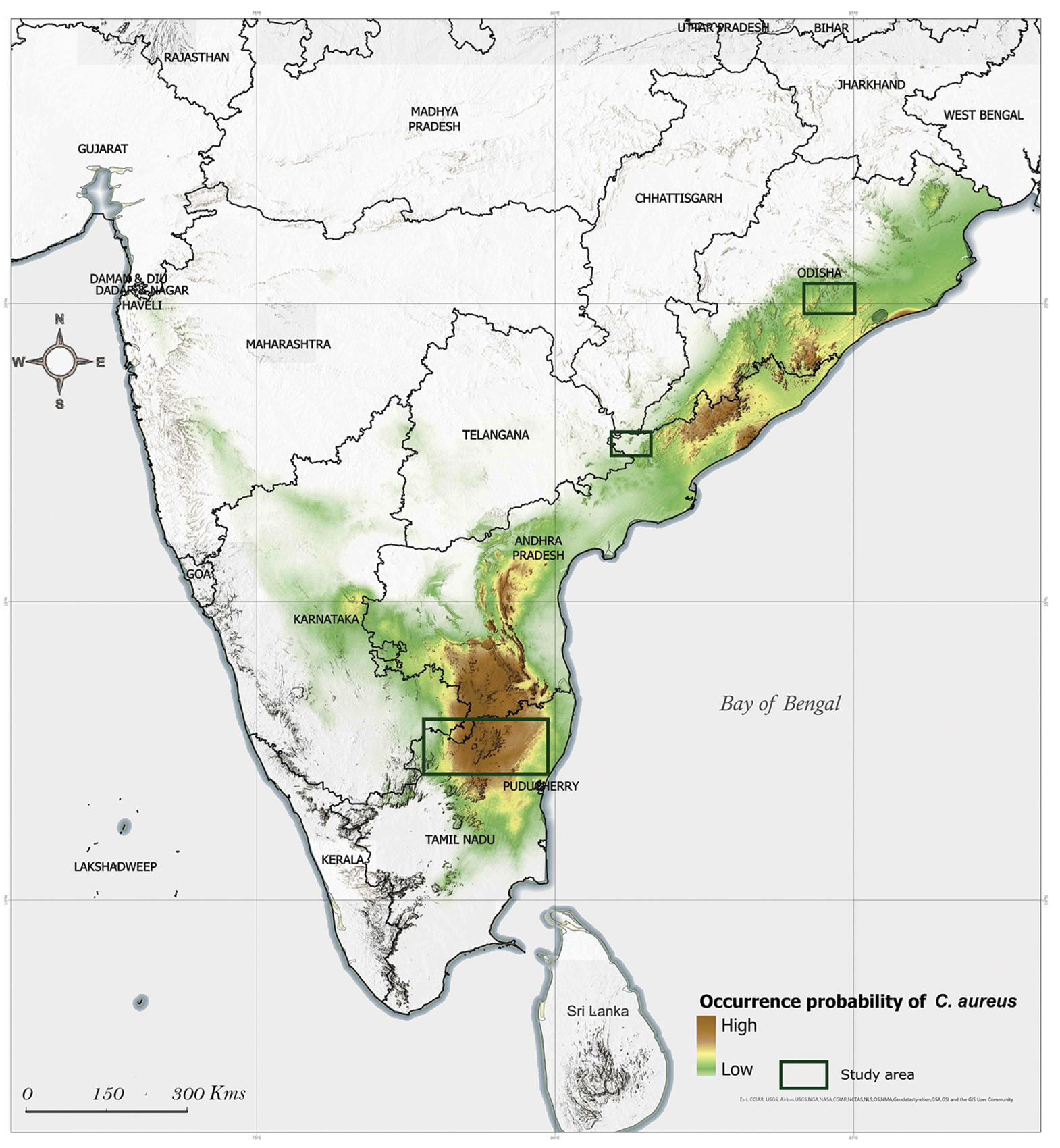

Recorded mostly in the Eastern Ghats of India, golden geckos have been found in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Odisha. Photo: Distribution information: Anukul Nath; Map composition: Debanjan Sarkar.

Discovered in 1870 and then 115 years later, Calodactylodes aureus is commonly known as the ‘golden gecko’ on account of some individuals, especially the larger, dominant males, having a pronounced, yellowish pattern. The females and other males have a highly mottled appearance with variable colours, ranging from reddish brown to black. Presently, the species is known from Vellore, Villupuram, Krishnagiri, and Tiruvanamalai districts of Tamil Nadu; East Godavari, Vishakhapatnam, and Anantapur districts of Andhra Pradesh; Kalahandi and Parlekhamundi districts in Odisha and Hampi district in Karnataka. The following are accounts of this lesser-known gecko by three different teams working in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha.

When Rare Turned Common

By Anukul Nath and A. Kalaimani

We heard the typical “kek kek kek… kek kek kek kek…” call of a gecko. Much louder than the house gecko we commonly hear in our homes, the effect was somewhat like a symphony. Many visits later, we honed in on one of the rock boulders and discovered a few bright yellow coloured, medium-sized geckos, together with some smaller, brownish ones – almost the size of house geckos (around 50-60 mm.). The adults had distinctively large heads with broad, rounded snouts. It was our first encounter with the species. On examining the images we took, we noticed unusual digit (finger) patterns, which displayed a unique expansion, much like a trapezoid. The pattern was the same, irrespective of the colour of the individuals.

This was 10 years ago when we were working on our Masters with Anbanathapuram Vahaira Charities (AVC) College, exploring sites in the Gingee Hills, along the undulating and hot terrain of the southern-Eastern Ghats of Tamil Nadu. Away from well-studied Protected Areas, we wanted to explore wildernesses that we believed would throw up rare and elusive species.

We were curious to unravel the species’ identity. As beginners in biology, we began our search with The Fauna of British India – Sauria by Malcolm Smith and were able to identify it as the golden gecko Calodactylodes aureus. We learned that the genus Calodactylodes in Latin refers to ‘beautiful fingers’. This genus constitutes another species in Sri Lanka, Calodactylodes illingworthorum. We also learned that the Indian golden gecko was described in 1870 by Richard Henry Beddome, a British Military Officer who became the Conservator of Madras Forest Department in colonial India. He had the distinction of collecting and identifying 10 specimens from the North Arcot district of Madras Presidency. Then, after 115 years, the species was rediscovered from the Tirupati hills, Chittoor district of present-day Andhra Pradesh by J.C. Daniel and a team from the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) in 1985.

Golden geckos are found in different hues, from reddish brown to bright yellow. The males take on a golden yellow hue during the breeding season, and hence their name. The females tend to be brown, with lichen-like patches on their body. Photo: Dr. Chethan Kumar Gandla.

In the next two months, in search of the golden gecko, we visited Melthiruvadathanur, Karadi Parai and the Sathanur Dam in the Tiruvannamalai district, the Gingee Hills in the Villupuram district and the Kailasagiri Hill (Ambur) in the Vellore district of Tamil Nadu. We recorded several geckos, in Reserved Forests, privately-owned areas and some pilgrimage sites. We encountered them in rocky caves and crevices of large rock boulders, where they would hide out during the day. Possibly the temperature in those microhabitats was slightly lower and the humidity higher than the rocky surface outside. Comparatively, large numbers of geckos were spotted in the caves where water seeped from the rocks. Spotting them was easier once we learned to distinguish the calls of these very vocal reptiles, particularly just before sunset. Besides their distinct call, another clue was their choice of egg deposition sites. These geckos lay eggs in communal sites on rocky surfaces. We spotted over 200 such sites, that harboured between two and over 250 eggs!

Smaller-sized eggs range between eight to 13 mm. in diameter. Later, Kalaimani found huge, empty egg masses on the roof cave at Yelagiri foothills. Egg-laying periods vary within the present known distribution limit of the species. We noticed viable eggs between December and April in Tamil Nadu. We also came across other reptiles in the landscape such as Psammophilus dorsalis, Hemidactylus sp., Hemidactylus triedrus, Eutropis carinata and Lygosoma cf. punctatus. Among these P. dorsalis was more frequent than the others.

Our persistent efforts revealed several new localities of the golden gecko not previously reported. Here, the populations were severely fragmented. Many geckos were found on private lands such as the Melthiruvadathanur village, where we saw rock boulders being blasted for stone quarrying.

Golden geckos are Schedule I species according to the Indian Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972. Mainly found in rocky habitats, their survival is threatened by rampant rock quarrying for granite along the Eastern Ghats. Photo: A. Kalaimani.

Currently the species is only known from four states of India (Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka). Even as we work to study it and secure its future, we know it faces serious anthropogenic threats such as mining in the Niyamgiri hills of Odisha and the construction of dams in the Papikonda hills in Andhra Pradesh. Shifting cultivation in Odisha and northern and eastern Andhra Pradesh pose yet more, virtually unchallenged threats to this elusive species. In Tamil Nadu, rock boulders are being blasted for construction, destroying vital golden gecko habitats in the process. Outside Protected Areas, the species faces unrecognised threats from encroachment and egg-collection due to mistaken beliefs by locals.

Despite being highly vocal and brightly-coloured, the Indian golden gecko has largely remained elusive. Owing to its rarity in the past, it is listed as a protected species and included in Schedule I (Part II) of the Indian Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972. Except for the Sri Venkateshwara National Park and the Papikonda National Park (Andhra Pradesh), all recent reports of the species are from outside Protected Areas. The golden gecko is precariously holding on to life with next to no protection.

The One Known as Bangaru Balli

By Chethan Kumar Gandla

"Look over the river bank on your right! Ruddy Shelducks Tadorna ferruginea, widely known as Brahminy Ducks!” exclaimed my colleague. These migratory birds are easily recognisable, as they hunt along waterbodies, wings spread, displaying their brown under-bellies. Sighting the ducks, I craned my head to see the mighty mountains on either side of the bank. Floating on the Godavari river in a boat through the Papikonda Wildlife Sanctuary, on a misty May morning is quite an experience and an invitation, an anticipation for what the day would bring. On top of my bucket list was the sighting of the enigmatic Indian golden gecko (bangaru balli in Telugu).

An hour into our boat ride, we alighted at Perantalapally, a village with several dozen households and a couple of temples. The serene spot, with its picturesque hill streams, was popular with the local film industry. A 20-minute hike later, in a spot flanked by huge granite boulders along a stream, we spotted our first Calodactylodes aureus. As expected, we found several more, their communal egg clutches attached to the rock surfaces confirming that this was the height of their breeding season (April to June – egg laying periods of the golden gecko vary within the present-known distribution limit of the species).

My subsequent visits to find golden geckos ended with mixed results. The Forest Department subsequently fenced the location, a vital move to stop anthropogenic disturbance. I was disappointed at not being able to sight the species or recent remnants of communal egg deposition sites, but even more worried that despite the fencing, tourism activities were ongoing.

Large dam projects in peninsular India such as the Polavaram Dam in Andhra Pradesh and the Kuppanatham Dam in Tamil Nadu threaten to submerge large swathes of forest land in the Eastern Ghats. Photo: A. Kalaimani.

The Polavaram-Indirasagar Irrigation project is being built on the Godavari river near Ramayyapet village of Polavaram Mandal, West Godavari district. On account of the proposed construction, during the state bifurcation of then-united Andhra Pradesh, seven mandals (tehsils) belonging to Telangana were merged into East Godavari and West Godavari districts and their administrative powers have been transferred to Andhra Pradesh. These seven mandals could be submerged and their backwaters accumulated with the proposed dam construction. The project proponents claim that it will irrigate 24 lakh acres in Andhra Pradesh.

The dam construction will be the largest human displacement so far, probably bigger than the Sardar Sarovar Project on the Narmada, affecting the largest population of Scheduled Indigenous Tribes, and the largest forest submergence, including parts of the Papikonda National Park and the biodiversity it is home to. Implications to the flow of Godavari river will be phenomenally irreversible, affecting the estuary, mangroves on the south-eastern coast and shall result in the mouth of the estuary shifting. And the plight of the golden gecko? With overwhelming odds stacked against it, even before we have an opportunity to study this interesting reptile, we might lose it forever in this area.

Finding the Newly Hatched and Some Field Nostalgia

Text and Photographs by Vivek Sarkar

May in the coastal state of Odisha can be unbearably hot and harsh. Conversely, the northern Eastern Ghats in south Odisha is a delightful escape from the heat waves, its rich biodiversity an opportunity too good to miss for naturalists, field biologists and nature enthusiasts. In 2013, I was in one such place, the Barbara Reserve Forest of Khorda district to assess the biodiversity of the area. I explored forest trails, climbed waterfalls, hiked in the hills with sharp eyes and ears, day in and day out, honing my field biologist skills. I encountered many interesting life forms and natural phenomenon, such as a nest of a king cobra Ophiophagus hannah, a Madras treeshrew Anathana ellioti, mock viper Psammodynastes pulverulentus, tree frogs Polypedates leucomystax, Oriental Dollarbird Eurystomus orientalis, violet awl butterfly Hasora leucospila and many more. But the most baffling find was the small, calcareous, flat, convex stone formations on the limestone walls, close to waterfalls and water seepages. They somewhat resembled the egg case of certain spiders but yet, they were hard as stone. Sometime, I would find them in very small patches, as many as three to four, but often the entire wall was covered with them! In June, I spotted a crack in one such “stone structure.” It took almost no time to recognise the reptilian snout arising from the feeble stone crack… the rock came to life! The snout stayed in this position for a long time. After a prodigiously long wait, the animal came out of the shell at lightning speed and fell on the muddy floor. This was the first time I saw the hatchling of a golden gecko. I had been seeing male and female golden geckos but did not know about their community nesting until then.

Vivek Sarkar found many small, calcareous, flat, convex stone formations on the limestone walls close to waterfalls and water seepages.

These geckos select their communal egg-laying sites carefully, considering favourable temperature and relative humidity for hatchling development. They shift sites after some time as a brownish green fungus or lichens grow on the new and old egg shells after a while. The bright, golden coloured males have a crackling sound that they emit during dusk, whereas the brown females with lichen-like patches on their body remain on the crevices of these stone formations. Their crackling calls comprise multiple, near-equidistant peaks that sounds like harsh drumming. While returning from the forest in the evening, my walks were made nostalgic with the calls of these magnificent yet elusive geckos.

These geckos may appear quite abundant in the landscape but if the trees are cut, or the torrential rivulets are clogged upstream or the stone formations are hindered, they stand to lose their favourable egg-laying sites, which can potentially make them vulnerable. Protecting just one site might not be enough to protect the species as they change their mass egg-laying sites after a period of time and would require similar sites with optimum conditions in close proximity. Giving umbrella protection to the entire forest would secure their future, as potential egg laying sites and also the array of entomofauna, their food source, would be secured.

It was only when he spotted a crack in one such “stone” structure that he recognised them to be egg clutches of what he later discovered were golden geckos. Golden gecko females find moist, rock surfaces to deposit their egg clutches, forming community nesting sites.

A discontinuous range of mountains along India’s eastern coast, the Eastern Ghats stretch from the Mahanadi basin in the north to the Nilgiri Hills in the south, covering 1,750 km. and spreading over 75,000 sq. km. The Eastern Ghats runs through the states of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Maharashtra, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh. With an average elevation of 600 m., its highest peak is the Shevaroy Hill that reaches 1,700 m. The Eastern Ghats support a rich array of tropical forests including pockets of moist deciduous, evergreen and semi-evergreen forests. This region contributes significantly to both species richness and endemicity. Relatively understudied, our understanding of the importance of herpetofaunal diversity and natural history in the Eastern Ghats is minimal compared to the Western Ghats.

The Indian golden gecko’s habitat is primarily the Eastern Ghats. The genus (Calodactylodes) is considered to be a Gondwana relict, and represents one of few scleroglossan lizard lineages that are strictly endemic to peninsular India and Sri Lanka. The species is threatened by various anthropogenic factors such as mining in Niyamgiri Hills of Odisha and construction of dams in the Papikonda Hills.

Shifting cultivation in Odisha and northern and eastern Andhra Pradesh is also a threat to the species. In Tamil Nadu, rock boulders are being blasted for construction of roads and for buildings near Vellore town, and the metal manufacturing industries are also destroying prime golden gecko habitats. Outside the Protected Area network and areas under Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the species faces high risk of encroachment (e.g., Anantagiri Hill in Andhra Pradesh) and clearing of eggs by locals.