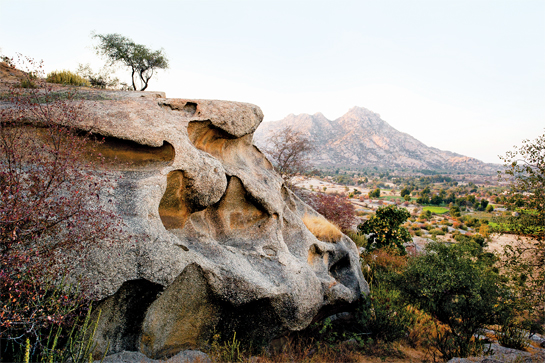

Grow Fast And Die Young - The Accelerated Life Of A Jawai Leopard

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 35

No. 7,

July 2015

Following the leopards of Jawai over two years has led Adam Bannister to believe that these felines lead relatively short lives owing to the unique landscape that is their home.

Photo: Adam Bannister.

In late 2013, I saw a female leopard in Jawai, in the Pali district of south Rajasthan, raising a litter of two cubs, while she still had a 16-month-old youngster from a previous litter. The three cubs were often seen together. When I returned for a second season in the second half of 2014, I came across the same female with yet another litter, and the previous cubs still very much a part of her life.

It did not stop there. On a camera trap, I managed to photograph the same female mating with a male while her then four-month-old cub watched. Incredible! In two-and-a-half years she had had three litters, and was showing signs of preparing for a fourth! In South Africas Kruger National Park, a female would be just about rearing cubs from a single litter to independence over the same period of time.

When I first arrived in Jawai, I spent many hours conversing with local villagers about the constant influx and surprising behavior of the area's leopards. Having worked with wildlife for five years in South Africa, I was used to a relatively stable leopard population in which large males held territories for eight years or more.

If the locals were to be believed, then it seemed possible that these leopards were not as territorial as their African counterparts. My initial suspicion was that the leopards moved flexibly, and shifted territories to align with the agricultural and pastoral landscape. However, after carefully observing the males in the area for over a year, I saw all signs of a territorial cat: scraping, roaring, scent-marking, and smearing of the facial glands on the walls of caves.

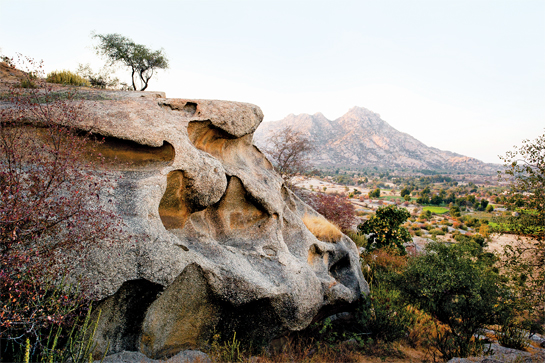

So what is the reason for this high turnover?

Photo: Adam Bannister.

TERRITORIAL MALES

Infanticide is well-documented amongst big cats. Once a new male leopard arrives on the scene, he usually kills the cubs and inseminates the female as soon as he can. After the death of a litter, it usually takes as long as six months before the mating process starts again. This delay allows the female to evaluate the fitness of the new male and to ensure stability in the area. When Nainas (another female leopard) previous cub (from a litter of one) was killed by a male in late March 2014, she began to mate within 10 days. These examples show that the interval between mating/littering among the Jawai leopards is short.

A series of sightings of a male leopard born in April 2013 also gave me insights into the growth rate of these leopards. After 19 months he had left home and by the 20th month, we saw him exploring areas as far as 10.5 km. from his birth hill. Even before his second birthday, he had become a fully-independent leopard. Although not unheard of in Africa, it is certainly a relatively short time period for a male to reach independence.

In March 2015, I saw a large male leopard limp into a cave - it was Bhero, a newcomer to the area. He was about five to six years old. I slowly drove forward and about 200 m. away, I saw a second male leopard, seemingly asleep, sprawled out on the rocks in the early morning sun. I was surprised at how close I could approach this leopard, without him even lifting his head. A quick look through binoculars and I immediately knew something was wrong. His body was still and his paws covered in blood.

He was dead.

I have worked with big cats for many years and have seen dead animals on many occasions, but nothing could have prepared me for this. I climbed out of the jeep and walked towards his motionless body - he was lying on his side and his pelt was shining in the sun. His body was still soft and warm. Every leopard has unique rosettes and spot patterns. It took me only a split second to recognize Nag Vasi, my favorite leopard in Jawai, and the father of Naina's cubs.

I had to hold back the tears. This was the male I had spent a lot of time with during my months at Jawai, tracking him countless times. I knew his favorite paths, his caves, and his watering holes. I knew where to look for him on these ancient hills and the time of day he would usually move about. Initially, he would run away when I got within 200 m.; a year-and-a-half later he would let me park 20 m. away. Our relationship was founded on respect. And just like that, he was gone.

It was obvious that he had been in a brutal fight. His body was covered in scratches and puncture wounds. When big cats fight it seldom ends in death; one protagonist almost always gives up and makes a run for it. If a cat is to die, it is usually due to the subsequent wounds; they crawl into caves or thickets to die quietly and out of sight. The death of Nag Vasi was different. He had obviously been killed on the spot - out in the open on the rocks - his skull fractured and throat crushed.

His death allowed me to have a closer look at his body - his extremely long tail, his powerful leg muscles, and his phenomenal physique. His condition was magnificent. It also allowed me the rare opportunity to try and estimate his age. I guessed he might have been around eight-nine years old, and the Forest Departments' official post-mortem declared him to be in good condition aged approximately 10. He was huge, but not old!

Just a few days after the death of Nag Vasi, one of Naina's current three cubs was separated from her mother. Bhero was seen, nose to the ground, following the scent of the helpless nine-month-old sub-adult female. By ‘normal standards, I would say that these cubs are doomed, far too young to survive independently, but among the Jawai leopard population, I cannot be sure. I witnessed Naina leaving her cubs for extended periods of time when they were as young as four-months-old. She also had a habit of only ever taking food to two cubs, leaving the third to fend for itself.

Photo: Adam Bannister.

ACROSS THE GLOBE

I paged through my journals from some of the other big cat projects I was fortunate enough to have been involved in. In the vast Pantanal area in southern Brazil, Projeto Onçafari, a jaguar habituation team, had managed to follow the life of a wild female jaguar living on a cattle ranch. This female had learned to hunt cattle; cleverly following them, even as skilled cowboys moved the herd throughout the vast tracts of the ranch. She had her first litter of cubs at 23 months of age, 13 months earlier than what is accepted as the norm. I thought at the time (2013) that maybe it was the human presence that was making her mate and reproduce early. Now that I look back, it may actually be a similar story to the one I witnessed in Jawai.

In the Pantanal, the cowboys are constantly moving the cattle to different enclosures. One day a jaguar could have around 1,000 cattle in its territory and the next day they could have all moved. At Jawai, the Rabari (local herdsmen) move their livestock to various fields, rotating the area and giving the grasses time to recover. In both cases, farming activities have a major influence on the availability of food for leopards - this is in complete contrast to the situation at Londolozi in Kruger, where human activity has had very little impact on the animals.

In addition to the unpredictable movement of their key prey species (goats, sheep, dogs, and cattle), the large cats in both areas retreat to safe hideaways during the day to avoid contact with people. In Brazil, it is to avoid cowboys driving cattle, and in Jawai, it is to avoid the farmers. Although both systems are different, the big cats in both areas share the same limited and patchy distribution of prey and ‘places of safety. Jaguar hideaways are small, forested islands in the wetlands of the Pantanal; for the leopards, it is the caves on the granite hills. If a rival leopard, or jaguar for that matter, moves in and threatens a resident's hideaway, the animal is left with little option but to fight… often to the death!

Photo: Adam Bannister.

|

WHY DON'T THESE LEOPARDS EAT PEOPLE?

Could it be genetic memory, encoded deep in their DNA, the knowledge that killing man will result in retaliation? Could it be the respect the local people show these magnificent predators or an age-old belief that if a leopard kills your goat it is actually a good omen for the coming year? There are many theories as to what turns a big cat into a man-eater, but one of the more widely-accepted explanations lies in the age of the cat. Often the cats are old, injured, malnourished, and in poor condition. Autopsies of man-eaters often reveal broken jaws or missing canines. Injuries sustained through general wear and tear and fighting. I believe that the leopards at Jawai do not live long enough to have to start exploring the concept of eating humans.

|

A UNIQUE HABITAT

Of the 29 individual leopards I have seen at Jawai, not one has been over 10 years of age. In South Africa, we regularly have leopards living beyond 15 years, some even as old as 18.

These observations and records paint a picture of a possible undercurrent that could be at play in Jawai. Is it possible that the pressures on the leopards, brought on by the unpredictable movement of prey, human involvement, and limited hideaways are forcing the leopards into a shorter and accelerated life?

On arrival at Jawai, I assumed that leopard mortality rates would be low; after all, there were no lions or tigers, and only very few striped hyenas to threaten them. Here the leopards are at the top of the food chain. In the last 17 months, in an area of roughly 60 sq. km., out of the 29 different leopards I recorded, 13 are either confirmed dead or have not been seen in the last six months. Presumably, they have been killed or pushed out.

With not a single known story of human malpractice, I believe that in Jawai the pressures and conflicts by leopards on leopards are exceptionally high. Judging by the wounds inflicted on Nag Vasi, I would say the battles are fierce. A highly competitive leopard population will result in the high turnover of animals that the local villagers had initially told me about.

The ultimate goal of a big cat is to reproduce. My theory - based on these observations - is that given expectation of a short lifespan the Jawai leopard may as well mature young, mate young, mate often and go down in a big fight. Leopards are widely regarded as the most adaptable of the big cats. But does this adaptability go as far as changing their biology and internal clocks to suit a specific environment and landscape? Possibly.

Follow Adam Bannister's work at www.adambannisterwildlife.com

Photo: Adam Bannister.

|

SHOULD WE COLLAR THE JAWAI LEOPARDS?

Collaring some of the Jawai leopards with GPS collars would allow us to understand home ranges, movement, habitat use, diet, dispersal distances, and corridors. But sometimes science has to take the back seat. The Jawai landscape, a matrix of ancient granite domes, community grazing-lands, mustard fields, and small villages is so incredibly delicate in its existence. Is it possible that the landscape and the characters are simply too fragile for such an intervention? After having observed the sensitivities at play here in Jawai, I believe that the way to save the leopards is to preserve the traditional way of life of the local Rabari people. Collaring animals will interfere with this delicate balance and, despite the scientific and useful information we could glean from GPS data, it just may not be worth it at Jawai.

|

Author: Adam Bannister, First appeared in: Sanctuary Asia, Vol. XXXV No. 8, August 2015.