Life, Water And Conflict: A Bear Valley Camp Waterhole Story

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 43

No. 6,

June 2023

Text and Photographs By Salil Dalvi

The transition zone between a forest and human settlements is often fraught with conflict and a tussle between species. Over the last five years of our stay in the rustic and wild landscape of Jhinna village, located in the buffer zone of the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, we learnt a satisfying lesson from our experiments: human-animal interactions need not end up in tragic losses for any of the creatures involved. Simple data and research-backed interventions are all that we need sometimes.

In a wild, conflicted landscape, Bear Valley Camp is located on the periphery of the Panna Tiger Reserve. Back in 2017, when we first visited our campsite, little did we know the adventures that lay in store for us. My wife, two daughters and I were fascinated and in awe of the wildlife around us. Yet we were not surprised when we heard about the first case of a leopard attack in one of the fields behind the camp (away from the forest). Human-animal conflict was a much discussed and read item for us city dwellers, but it was our first encounter in such close proximity. Even after that, we let such incidents slide as simply a case of something that one needs to be accustomed to or deal with when one lives in close proximity to the forests and has livestock at home. I find it strange today as back then, even the people who were impacted by such animal interactions had come to terms with the situation and accepted it as their fate.

But as the tragic incidents kept piling up with alarming frequency, it started to dawn upon us that there was something seriously wrong here, as the cases were not just related to leopards, but also sloth bears and hyenas. This clearly was not just about food, there was something else afoot.

A bird’s eye view of Jhinna village as seen from the forest, with the Bhapatpur dam in the background.

Needless to say, situations such as these create havoc and panic amongst locals and also result in anger, often with an objective of exacting revenge against the animals, who they believe have wronged them. Tensions ran high and every kill or incident needed to be carefully investigated. We were also one of the affected – we lost our dog to one of the poisoned kills. Sheru was a stray who used to live in the camp, and as is the case with all strays around the fringe areas of the tiger reserve, he had absolutely no issues with consuming raw meat. I was frustrated and angry but helpless at the same time as it was impossible to find out who was responsible. The loss of every single livestock was accompanied by the long-drawn procedure of compensation, but then that was never enough and served as too little, too late.

The author built a waterhole near his residential camp for wildlife to slake their thirst and was delighted when this male leopard waited patiently a few metres away, as he replenished the waterhole.

Water Woes

Our stay at the Camp also gave us a real-time experience of what living in a dry deciduous forest entails, and how easy or harsh it is for animals to survive in such areas. During this period, I walked long distances, covering almost every inch of the forest around our camp (almost 50 sq. km.), surveying all possible areas and recording minute details. The result was alarming – the forests in the immediate vicinity of Jhinna village did not have a single waterbody that remained active after October-November; there were no rivers or ponds inside the forest, and the ones which were present were simply too far away.

The only option for the animals was to approach open wells or cattle drinking troughs inside the fields, or to make their way to the Bhapatpur dam, which was a couple of kilometres away from the forest. Both these exercises entailed crossing fields, roads and villages.

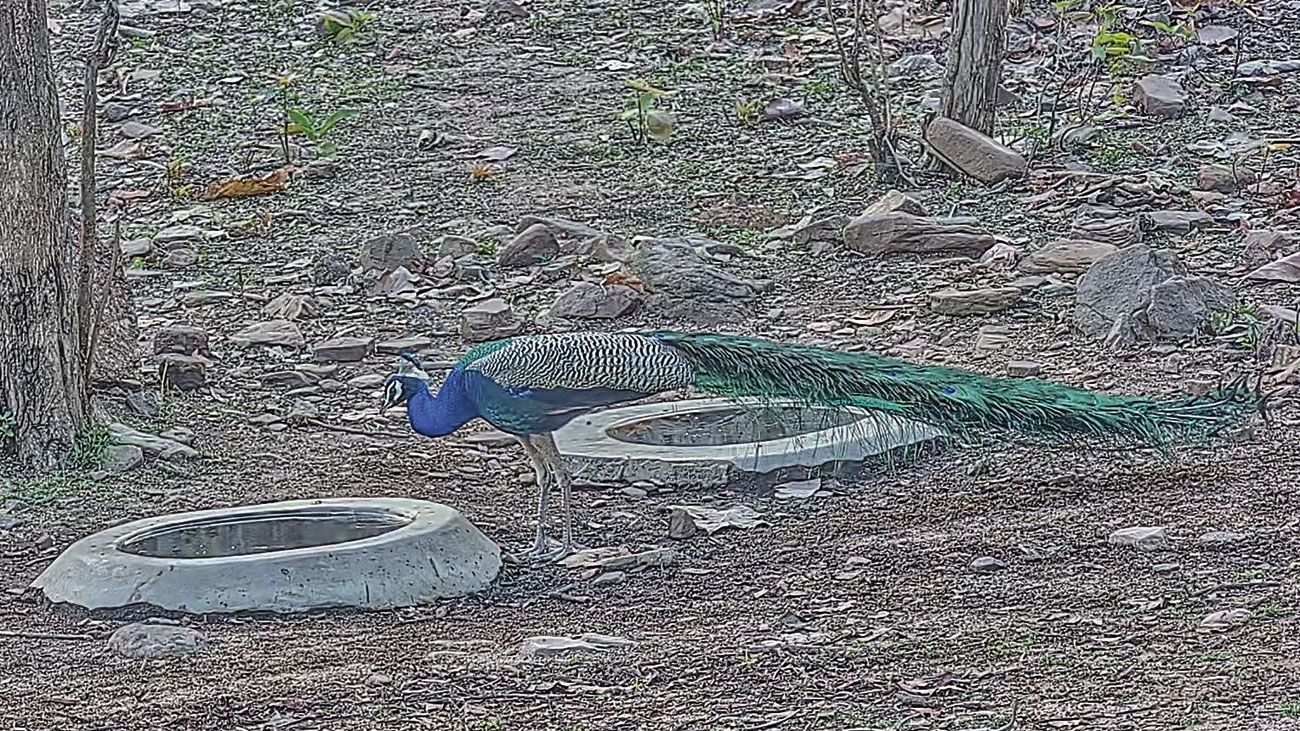

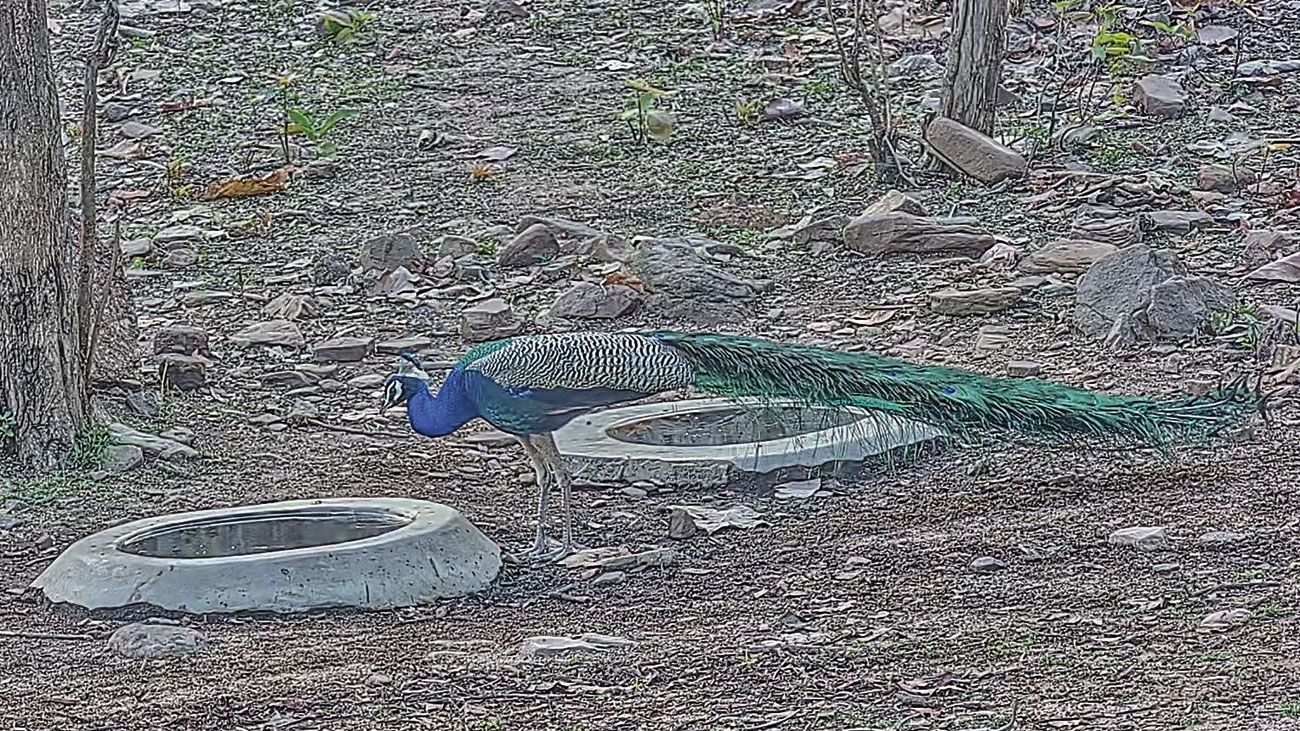

The forests in the immediate vicinity of Jhinna village did not have any waterbody that remained active after October-November. The only option for animals was to drink at open wells or cattle-drinking troughs or make their way to the Bhapatpur dam, all of which involved crossing fields, roads and villages that led to conflict with humans and the occasional killing of livestock. This calf was lucky to live to see another day. The waterhole built by the author met a crucial need for wildlife such as this peacock and reduced conflict situations.

People live in the fields in the buffer region here, guarding their crops day and night, sometimes with their entire families. This forced humans and animals to meet, which, not surprisingly, led to the conflict. Fortunately, there were no fatal attacks but innumerable cases of mauling, angry charges and the occasional killing of livestock.

Roughly 18 or 20 months from the time we moved our base to the Camp, we began comprehending the complexity and contours of life in Jhinna. By then we had spent two full monsoons and almost two dry seasons there. We now had enough data and an insight into the dynamics of human-animal interactions.

The author’s waterhole experiment was born from a genuine desire to prevent frequent attacks, and evolved into a safe harbour for wild animals, and a very welcome coexistence.

Animals largely approach particular places for territory, food and water. The latter two influence the first, and we thought that if we were able to eliminate or replan the hazards associated with food and water, the risks could be diminished. We certainly would not seek to influence the territoriality of apex predators, and in any event if one moved into a competitor’s territory, conflict would likely ensue.

We documented over half a dozen different leopards, five individual hyenas, two male and, possibly, three female sloth bears.

Piecing together all we understood and read about the region, we decided to build a waterhole outside our camp, which we planned to replenish on a daily basis. The intention was to create an alternate source of water hoping it would prevent animals from approaching human habitation to slake their thirst. We had no idea how it would turn out, but we built one anyway.

The forests in the immediate vicinity of Jhinna village did not have any waterbody that remained active after October-November. The only option for animals was to drink at open wells or cattle-drinking troughs or make their way to the Bhapatpur dam, all of which involved crossing fields, roads and villages that led to conflict with humans and the occasional killing of livestock. This calf was lucky to live to see another day. The waterhole built by the author met a crucial need for wildlife such as this peacock and reduced conflict situations.

And that marked the beginning of one of our most epic adventures.

A New Joint In The Forest

After the waterhole was completed in October 2019, the beginning of the dry spell, despite the scarcity of water, the animals did not make a bee-line for it. The first animal came after nearly a month, a lone hyena that had stopped for a drink. It wasn’t that animals were not present in the area; they crossed the waterhole almost every single day, but never stopped to drink. This showed us how careful and habit-oriented wild animals are.

In the first few months, animals would stop by every couple of weeks, but eventually more began visiting the waterhole. Nocturnal and diurnal animals – domestic and wild, visited the water source.

Visitors on official night safaris often reported seeing nocturnal species not seen during day time safaris. With this increased traffic, it became all the more important to ensure that animals were not disturbed, and extra effort was made to ensure their security.

Nocturnal and diurnal animals – domestic and wild – visited the waterhole and soon it became one of the surest possible ways of spotting rare and elusive animals including the leopard, hyena and sloth bear.

This story started out as a human-animal conflict one, but our biggest win turned out to be the cessation of such conflict! The availability of water dispelled the need for animals to cross farms to reach the dam, or visit the cattle troughs.

Of course, the odd case of a leopard taking off with a goat or a dog would take place, but those were opportunistic hunts. Frequent conflicts vanished.

Coexistence

Initially, we would monitor the waterhole using (non-flash) motion sensor, infra-red cameras. As the years flew by, however, we realised that better quality equipment was needed to document wildlife behaviour. We therefore procured a high-resolution night vision camera, which is capable of taking images in pitch darkness without a light source.

This demonstrated graphically that peaceful coexistence with wild animals was indeed possible, provided we took necessary and carefully thought-out steps. What began as a genuine desire to prevent frequent attacks evolved into a safe harbour for wild animals, and a very welcome coexistence.

To reach this point took more than merely building a waterhole. We had to be vigilant, dedicated, and willing to deal with any and all situations in a remote rural area where incremental weather often led to power outages for days on end.

Nocturnal and diurnal animals – domestic and wild – visited the waterhole and soon it became one of the surest possible ways of spotting rare and elusive animals including the leopard, hyena and sloth bear.

It’s over four years now. Time enough to conclude that the waterhole experiment has succeeded. We found ourselves moved in more ways than we ever imagined. The understanding and knowledge gained was immeasurable, the data collected priceless… and the moments beyond special.

Over the last few years, we have had fairly close encounters with many animals while filling the waterhole. Sometimes, it almost felt like they recognised us and felt no threat. I once remember cleaning dry leaves and other debris from the waterhole, and looking up to see a magnificent male leopard sitting about eight metres from me, on the game trail, which led to the waterhole. He made no attempt to hide or run, just sat waiting for the waterhole to fill and for me to leave, so he could drink in peace.

_C-1300_1686043411.jpg)

Nocturnal and diurnal animals – domestic and wild – visited the waterhole and soon it became one of the surest possible ways of spotting rare and elusive animals including the leopard, hyena and sloth bear.

Nothing in my experience comes close to the feeling of standing peacefully in close proximity to a leopard. Of all the things one does in life, there are a few that deliver lasting, unadulterated satisfaction and joy.

The waterhole was ours.

Salil Dalvi An ex-pilot turned IT professional, who moved back from Germany, he left a successful IT career to pursue and work on wildlife conservation and photography. He lives and spends most of his time at his forest abode and jungle resort, Bear Valley Camp at the Panna Tiger Reserve.

_C-1300_1686043411.jpg)