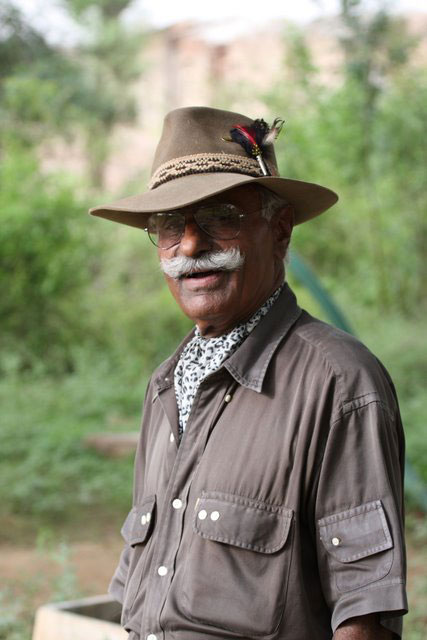

Meet Fateh Singh Rathore

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 28

No. 4,

April 2008

Photo: Tiger Watch.

More than almost any other person, the life of Fateh Singh Rathore is synchronous with the lives of tigers. Having saved a place - Ranthambhore - when everyone believed it was no longer viable for tigers in the 1970s, Rathore found his lifes work in protecting a species with which he fell hopelessly in love. This is an extract of an interview conducted by Jennifer Scarlott of Sanctuary magazine that covers the history of Ranthambhore and todays struggles for the tigers future. For the full text, log on to www.sanctuaryasia.com

Were you always in love with the tiger?

People arent necessarily born with a passion. Tigers came into my life when I was an adult. I had a love for nature, but I did not know I wanted to work in a forest, or do conservation work or that I was looking for the tiger. My way was already fixed by God. It started around 1960, when the queen of England came here.

That was when part of your job in the forest service was to ensure that foreign VIPs bagged their tiger?

Yes, the government issued hunting permits until 1969. But then, the great lady Mrs. Indira Gandhi and Kailash Sankhala, then director of the Delhi Zoo, decided the tiger needed protection.

Do you remember your first tiger sighting?

I saw the first tiger of my life when the Duke of Edinburgh shot it down. I was not in love with the tiger at the time. We were very happy that we succeeded in getting the tiger for the VIPs - we celebrated, actually.

And what took place subsequently?

In 1969, I was lucky to be part of the first group to be trained at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in Dehradun. I had nine months of training with S. R. Choudhury, a great man. The experience groomed me for another way. My life had finally begun.

During the second period that you were in Ranthambhore, in the early 1970s, you said you met Kailash Sankhala and M. Krishnan?

Yes, at the time the senior forest officers never lived here on location. I was actually the first officer trained in wildlife management, so I was told: “Do whatever you want." It was literally left to me to decide how to manage the park. Kailash Sankhala helped me prepare a budget and give shape to a management plan. M. Krishnan taught me photography. It was an adventure.

A dangerous adventure some might say. Tell me about your efforts to shift villages out of the park.

I knew there was no priority more urgent or vital than this. There were around 20 villages inside the park and virtually no tigers. By 1976, we had moved all the villages out and tigers began to move in.

Photo: Gertrud and Helmut Denzau.

Photo: Gertrud and Helmut Denzau.

It was that easy, was it?

No! It was one of my most difficult assignments. The people hugged the trees and wept. They felt that their future was utterly bleak. All the old people said, “We have already passed our entire lives here, let us die here." I was crying with them because, inside me, I knew they were paying the price for something they may never understand. We laid out plans for the resettlement site called Kailashpuri and allotted plots by a lottery system. With the people gone, nature responded beautifully. Not just the tiger, all the animals that had been driven out by humans years ago returned.

What was Ranthambhore like before this shift?

The beds of the three lakes where people see all the wildlife today were farms where water chestnuts and wheat were cultivated. There was very little water for wildlife. There were shops near the Fort! Everywhere you looked, there were agricultural plots. The forest was completely denuded by cattle, by people, by lopping and browsing. You couldnt see a blade of grass on the ground. There were 96 villages on the periphery - 2,00,000 people and an equal number of cattle. People used to camp everywhere. At night, if you climbed the Fort and looked out over the entire park, you saw nothing but campfires. Every hilltop was occupied. No one today can even imagine what it used to be.

So how come such a site was even selected to be a part of Project Tiger?

You know, history should thank M. Krishnan for this. He fell in love with Ranthambhore and his vision helped strengthen my own. He became a member of the Tiger Task Force (in the early days of Project Tiger). At that time, Ranthambhore was small and unknown. I cannot recall any tourism in the early 1970s. Sankhala (who became the first Director of Project Tiger in 1973) said that at some point he would declare Ranthambhore as a tiger reserve. I responded saying: “No, I want Ranthambhore to be among the first." I talked to all the members of the Tiger Task Force, and asked them to allow me to use my training to solve Ranthambhores problems.

I presume that by now your life was almost totally focused on the tiger?

Not really, I was just convinced that I could make it a better park. But I did begin to see pugmarks on morning drives. Then, slowly, I began to see the tiger roaming in front of me during the day. I never expected that, because all the books I read had said that the tiger was nocturnal, solitary and elusive.

I am guessing the prey base was negligible too then?

Wild prey was scarce. Tigers seemed to have no shortage of cattle and buffalos. To put it mildly, people living around the park were not happy with the tiger.

Photo Courtesy: Sanctuary Photo Library.

Photo Courtesy: Sanctuary Photo Library.

And when did you see your first cubs here?

I will never forget the day. It was June 7, 1976. A tigress I had named Padmini, after my daughter, was seen by me with four cubs! I was wonderstruck and followed this family day and night. Initially, the tigress was unhappy with my presence, but eventually she began to trust me and seemed to treat me as a friend!

You were not yet the Field Director of the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, right?

I was officially appointed as Field Director in 1978 and I served for 10 years all the way to 1988. We even got Ranthambhore declared a national park. We tried our best to have it declared a World Heritage site, but failed. With the fort and the fact that Ranthambhore is still considered the tiger capital of the world, I feel the park should now, at least, be given this recognition.

Project Tiger was considered the worlds most successful conservation project, right?

Yes. In the beginning, Project Tiger was a fantastic success. Unbelievable. It was the finest example of a wildlife success, but slowly, a sort of rot set in and officers posted to this wonderland were carelessly chosen. Not only did some have no experience, but within two years, just when they might have started understanding what should be done, they would be shifted. This is why most parks deteriorate. Theres no accountability.

So a faltering administration and poaching combined to cause the decline?

Yes, the administration failed the tiger. As for poaching, frankly, we were never really able to tackle the root cause. Just catching a poacher and sending him to jail achieves nothing. He will get bail and continue poaching because he has no other means to live. We are trying to change that now by working with a group of Mogiya tribals who openly admit they have killed tigers in Ranthambhore. One man actually said he had killed eight tigers! God knows how many more are being killed. We are now using Mogiya informers to help nab others with help from the police and forest department.

Despite all this, Ranthambhore is doing reasonably well. Do you feel that the tigers long-term future here is assured?

No. To secure the tigers survival here, we must have a concrete plan with practical goals. The move to secure adjacent forests in Sawai Mansingh and Keladevi is good, but the villagers there must agree to shift if the plan is to succeed.

And the corridors that are so vital to tigers?

Without corridors, the long-term future of Ranthambhore will always be at risk. The forest department claims that Ranthambhore holds 32 tigers. I believe the number is lower, but in any event, to safely hold even 30 tigers as a breeding population, the park area must be expanded into the Keladevi and Mansingh Sanctuaries. The first task here should be to enhance ungulate densities in these new areas. The tigers will then follow their prey, as they did in the 1970s.

List your five top wishes for Ranthambhore

1. Corridors from the present core to Mansingh and Keladevi; 2. Enhanced prey base to prevent cattle kills; 3. Local communities to benefit directly from wildlife tourism; 4. Better coordination and cooperation between the Forest Department and the government and non-government agencies, together with a re-structuring of the department to promote harmonious work and 5. Transparency. Sariskas problems arose because of the cloud of secrecy over tiger numbers. Officers are afraid they will be blamed when tiger deaths translate to lower tiger numbers. Instead of concealing poaching incidents, the Field Director should use the incident to demand greater resources and facilities.

But surely its self-defeating to make up numbers. Can Ranthambhore be saved?

Today, even if people are falsely reassured that the tiger is fine, they tend to believe it. This has to stop. What we must communicate to them is that: “Your life will be miserable if the tiger vanishes." They must understand that their lives depend on the tiger. Today, virtually the entire economy of Sawai Madhopur is based on Ranthambhores tigers - 50,000 people depend on this animal. If tigers are being killed, everyone must know, so everyone can join the fight to save them. I believe it is still not too late. We can save Ranthambhore and we can also bring life back to Sariska.

First published in: Sanctuary Asia, Vol. XXVIII. No. 3, June 2008.

Photo: Gertrud and Helmut Denzau.

Photo: Gertrud and Helmut Denzau. Photo Courtesy: Sanctuary Photo Library.

Photo Courtesy: Sanctuary Photo Library.