The Giant Squirrels Of Palani

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 41

No. 12,

December 2021

By Sanjay Prasad Ganguli

It was not quite the island I had always fantasized about. This one stood at more than 2,000 m. above sea level, at the top of a chain of mountains – a sky island – the undulating grasslands dividing the unique high-altitude sholas, acting as a natural barrier to the movement of wild species.

I was here for my Master’s thesis and had travelled 400 km. from my hometown to the hill-station of Kodaikanal, my field station for two months as I worked on surveying the presence of the Malabar giant squirrel and its nests in the plantations of Palani Hills.

Large parts of the shola and grassland mosaic of the Palani hills have given way to monoculture tree plantations or agriculture. This has disrupted the arboreal lifestyle of the Malabar giant squirrel that is now forced to travel on ground between trees in the limited forests that remain, at great risk of being hunted.

Photo:Public Domain/Prabhu B. Doss

THE PALANI HILLS Ecosystems are living entities in their own right. They have active interactions within themselves in a multitude of ways – from prey-predator relations to mutualistic, parasitic, and several categories in between. What starts off as elementary mutations at the genetic level, over millennia results in differences in appearance and/or behaviour, even concluding in the formation of a new species, nearly all of which is aimed towards environmental adaptation.

Since the advent of humankind, however, the story has altered. The genetic changes that occurred in our ancestors resulted in a sharper mind that gave us the ability not only to adapt to the environment around us, but modify the world around us for our need (and greed). The landscape of Palani hills is one among many in the world that is victim to such transformations.

The Palani hills in Tamil Nadu belong to the Western Ghats habitat, rich in floral and faunal diversity. A mosaic of grasslands and shola patches can be seen across the chain of mountains, including the Anamalais. The Sky Islands, in the middle of this matrix of habitats, have a disproportionately higher number of endemics and is an important habitat to protect. Unfortunately, in the 19th century, long before the value of this habitat was understood, American missionaries and British civil servants transformed this area to serve their needs. Ever since, the Palani hills have been threatened by anthropogenic activities including conversion into plantations and agricultural lands. A major hub in this landscape – Kodaikanal, was established as a hill station in 1845, triggering drastic changes near the town, one of which was the creation of an artificial lake. The most disastrous change of all was the planting of fast growing and exotic timber species (that rapidly turned invasive as seen by their spread) such as Acacia mearnsii, Eucalyptus globulus and Pinus sp., converting grasslands and sholas alike into haunting monocultures. Additionally, a law passed in 1996 against tree felling of any sort, aided their rampant growth.

Malabar giant squirrels gorge on fruits, tree bark, flowers, and nuts and thus are effective seed dispersers. Omnivores, they also occasionally feed on bird eggs and insects.

Photo:Sanjay Prasad Ganguli

THE GIANT SQUIRREL The dense, low canopied luxuriant shola trees are bordered by waves of grasslands and exposed rocks. Step into one of these shola patches and you get a glimpse of native life as the eerie silence of a plantation is replaced by bird calls – nuthatches, minivets, flycatchers, and babblers, as they travel in a tight-knit feeding party. Their calls are drowned only by the Malabar giant squirrel’s metallic staccato chirrup.

Despite its loud call, large and animated bushy tail and contrasting colours of red and black, the Malabar giant squirrel Ratufa indica can be silent and elusive in the jumble of the thick canopy. An emblem of the Western Ghats, a wide range of colour variation exists amongst the subspecies – stark black and red to a more or less uniform rusty red. It prefers dwelling in the upper canopy, which is where it builds its nests. Large gaps in the canopy are traversed on the ground, a risky tactic that is becoming more necessary with the increase in deforestation. It builds several nests or dreys during its annual mating season between October and November. These dreys are a collection of dry twigs and leaves, all of which are found in their natural habitat, built in tree forks. Multiple nests help avoid ectoparasites, predation and also allow it to move throughout its habitat while raising its single pup.

The Malabar giant squirrel, also known as the Indian giant squirrel, measures about 25-50 cm. in length. Arboreal in habit, it builds large globe-shaped nests in tall and densely-branched trees, out of sight of its primary predators, birds and leopards. Endemic to India, it is found in the Western and Eastern Ghats and the Satpura range.

Photo:Sanjay Prasad Ganguli

Photo:Public Domain/Steve Eason

The Unilever Mercury Leak

Photo:Public Domain/Steve Eason

The Unilever Mercury Leak

After a three-month investigation, in March 2001, Nityanand Jayaraman, environmental writer and activist, and his colleagues exposed improper waste disposal practices of mercury waste at a thermometer manufacturing plant in Kodaikanal in the Western Ghats owned by Unilever, the London-based consumer products multinational. The Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board revoked the factory’s operating license and the plant was shut down later that year. However, workers continued to complain of health impacts, and soil and water samples revealed high concentrations of mercury. Unilever reached an out-of-court settlement in 2016 to compensate injured and deceased workers and their families. However, the company continued to claim that it did not dump glass waste contaminated with mercury and that it had sold glass scrap containing mercury to a scrap dealer and that there were no adverse impacts on employees or the environment. If this wasn’t bad to begin with, Unilever decided to fell 425 trees in their property in January 2020 exposing all its poisonous content to be washed off by rain, a frequent occurrence in this landscape. The risk now doubles in the neighboring Pambar

shola and downstream ecosystems that will receive the mercury from the soil in the defunct factory property. Though we are yet to study the effect of mercury poisoning on wildlife, it is something that is now inevitable. Through bioaccumulation, the mercury in the soil will soon show up in every resident of the food chain it sustains – including birds and squirrels. As for the fish, the mercury in the water turns to methylmercury, which is a highly toxic substance causing reproductive and nervous system disorders. In humans consuming such fish, it can have adverse effects on the nervous, digestive and immune system and also affect the kidneys, lungs, skin and eyes.

ADAPTING TO A CHANGING LANDSCAPE Once glorious stretches of shola forests and grasslands have been reduced to mere pockets today. My work looked at how this habitat specialist rodent has adapted to this dynamic changing landscape. Areas of pine monocultures seem to be of little to no use to the squirrel as they lack nesting materials and nesting space in their mighty forkless trunks. Meanwhile, every now and then we noticed a bolus shaped nest in the forks of eucalyptus trees. The towering eucalyptus presented the ideal height and branching for the squirrel. These were signs of its presence in some of these modified landscapes, highlighting how nature is trying her best to survive this invasion of colossal intruders.

Data collection over a significant area of the Palani landscape, clearly indicated that the squirrels were nesting in the plantations. The majority of dreys were found in eucalyptus trees, followed by another invasive species of the genus Alnus (both of which are trees that grow fairly tall), and finally in the shola trees. Despite the characteristic heights of the two non-native hosts (Eucalyptus globulus and Alnus sp.), the data suggested that the squirrels preferred them for their branching rather than their height.

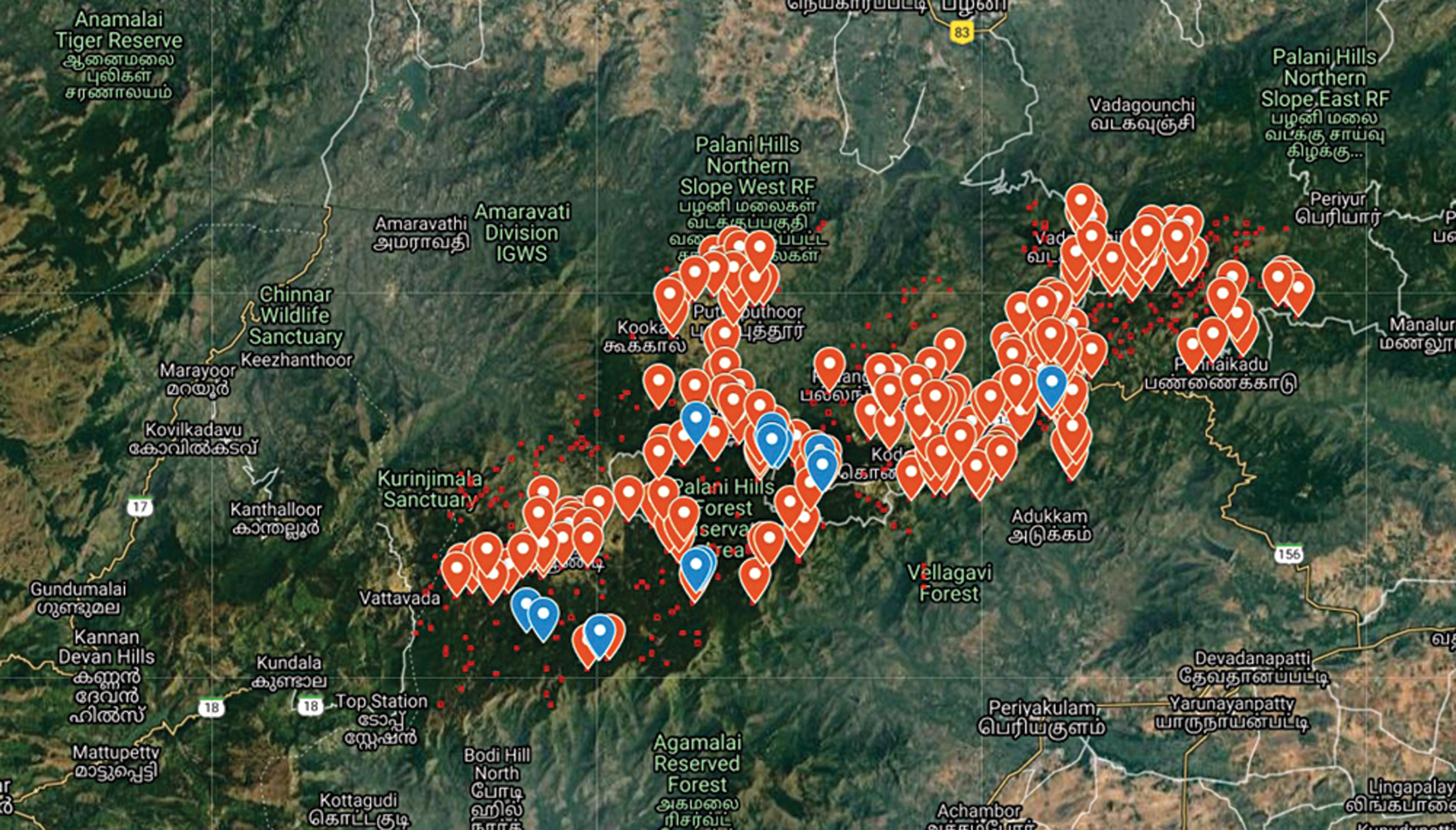

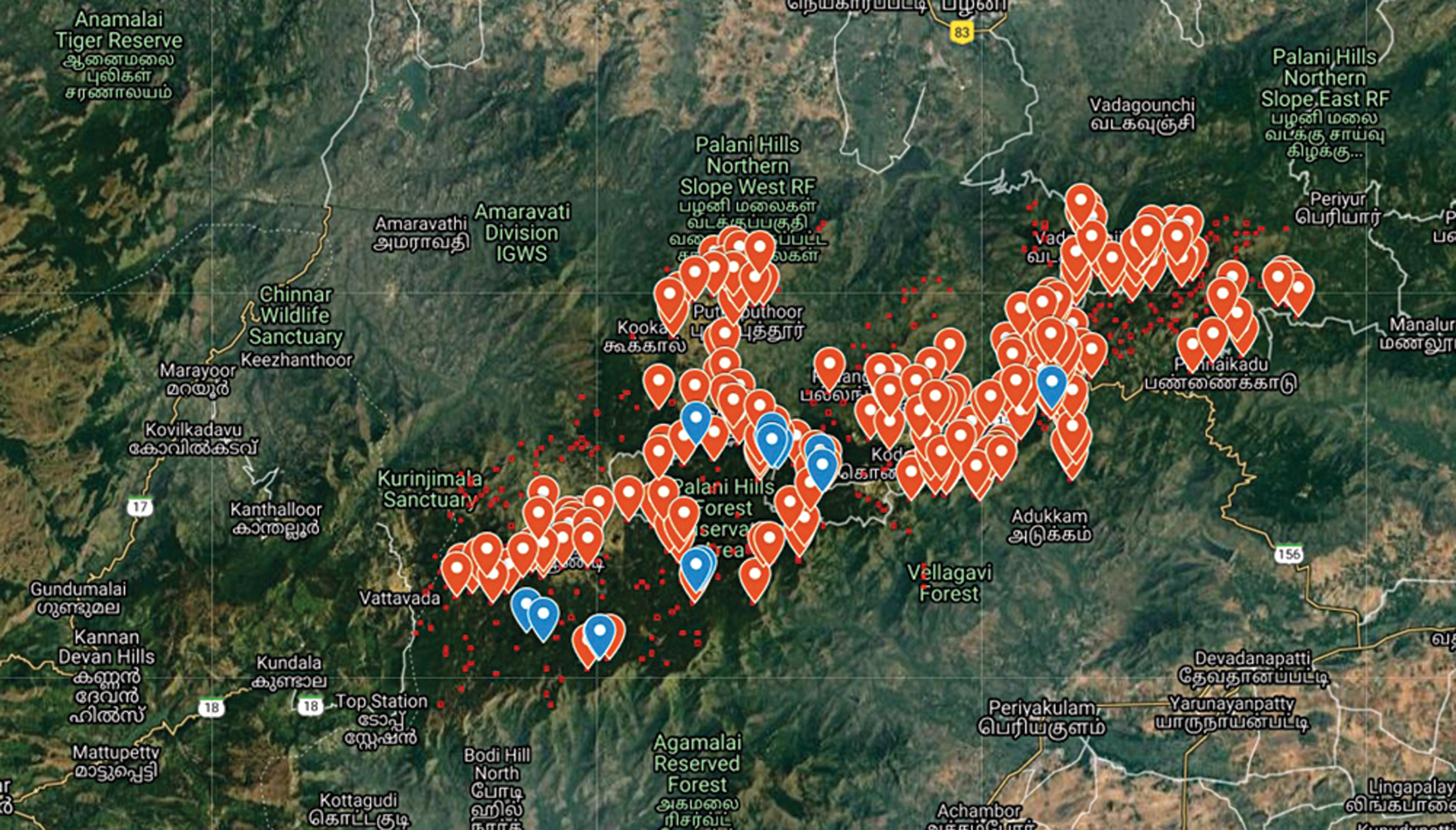

A map of the author’s fieldwork data sheet highlighting the centroids where plot studies were undertaken. This data is to be correlated with the absence or presence of the nests. KEY: Blue Markers – Nests found; Red Markers – No nests but plot work done; Red Squares – Additional plots yet to be studied. (The author completed 200 of the 500 originally projected centroids).

Many monoculture plots had a distinct understory dominated by indigenous trees. Further analysis of the data on the plots and their tree composition revealed a perplexing detail. We found a high density of adult Acacia mearnsii in every plot where the understory was rich in shola trees. Did the presence of acacia in the upper story somehow influence the presence of the native species that were previously thought to be completely eradicated from the site? This is a question that will require more research over a longer period.

While we know that the sholas are valuable for the Malabar giant squirrel that gorges on the fruit, flowers, and nuts, found here, the data allows for another observation – plantation plots with high acacia density may have a positive influence on the presence of the giant squirrels despite not being a good option for nesting.

While the results suggest that these squirrels are possibly adapting to their foster hosts, more work remains to be done to understand the finer details of what’s happening in this landscape. All through its range, the Indian giant squirrel is majorly dependent on tree composition in its habitat and is threatened on various levels – poaching, loss of habitat for timber, agriculture and vulnerability when crossing fragmented forest stretches on the ground. The Palani hills is one such highly disturbed habitat and one that we are only beginning to understand.

While the eucalyptus trees maybe used for nesting, they are ill-suited for these high elevations. Cyclone Gaja in November 2018 proved this point by laying waste large areas of eucalyptus, pine, and acacia. The shola patches contrarily withstood the high winds, as it is native to the environment they were built for.

The Sky Islands of the Western Ghats are a treasure trove of avian biodiversity with birdwatchers able to spot species such as the Black and Orange Flycatcher as seen here.

Photo:Sanjay Prasad Ganguli

A lot more variables and possibilities need to be examined in order to get a better, more in-depth understanding of the Malabar giant squirrel and its nesting preferences in a landscape that seems to be reverting back to its old growth. After completing 200 of the original 500 plots chosen, the results received are quite indicative of new and interesting changes in this landscape. Although a more thorough picture will surface only after completion of all the 500 plots, following my study, other biologists such as Amira Sophia is investigating calling patterns of giant squirrels in shola patches and plantations to better understand behaviour. My work ran parallel to another project by members of the same lab – Dhanesh Ponnu who examined the nesting habits of palm squirrels, and Aravind P.S. who is studying the occurrence of all squirrels on this plateau as well as others in the Western Ghats. Nandini Rajamani and her team in other parts of the country are recording essential data on small mammals – from the least concerned palm squirrels, to marmots and pikas of the trans-Himalayan landscape.

The Sky Islands of the Western Ghats are a treasure trove of avian biodiversity with birdwatchers able to spot species such as the Nilgiri Flycatcher as seen here.

Photo:Sanjay Prasad Ganguli

DISAPPEARING SHOLAS We have little idea of the kind of physiological or psychological effects habitat alteration of this level has on a wild species. Nature never rushes when it comes to restoring an animal population or its habitat. It takes several generations, several thousand years to bring about even the most basic modifications, while we would have spent less than the better part of a century in radically transforming this landscape. My two months in the field left me with a turmoil of emotions for the forest, its residents and human impact on their everyday life. My fieldwork had begun on a rather gloomy note witnessing the high level of degradation in my study site, as I had spent the earlier two weeks in the relatively undisturbed Malayan regions of Arunachal Pradesh. Like the play of mist and sunshine, my gloom too lifted in a few days as I began noticing the birdlife in these plantations along with the presence of squirrel nests. The sparse shola strands as opposed to the endless plantation ranges made me wonder of the density and diversity of life that once called the Palani range their home.

However, amidst all the doom, I also saw signs of hope. The young saplings beneath the army of invasive giants, the occasional whistle of the sholakili drifting through the monotony of the plantation and the canon-shaped bolus of the giant squirrels tucked in the forks of eucalyptus trees are all signs that nature is constantly attempting a comeback.

Sanjay Prasad Ganguli is a naturalist and wildlife photographer from Pondicherry who has been documenting wildlife and landscapes across India for the past decade, from the Himalaya to the Andamans, with a focus on lesser known fauna.