The Godawan Man Of India (1996-2025)

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 6,

June 2025

Walk into any lane in Jaisalmer and ask if they’ve seen a Godawan (the Great Indian Bustard), and Radheshyam Bishnoi’s name will almost certainly follow in the same breath. Radhe was the flag bearer of India’s desert conservation movement, carrying forward the Bishnoi community’s centuries-old devotion to protecting the environment.

Written by Gunjan Menon with anecdotes from Dr. Sumit Dookia, Nirmal Verma, Sumer Singh, Parth Jagani, Saiyam Wakchaure and Sharvan Patel.

On the night of May 23, Radhe, Shyam Nathani Bishnoi, Kanwaraj Singh, and Forest Guard Surendra Choudhary set out to do what they had done often in the past – intercept a reported chinkara poaching attempt. But they met with a tragic accident on their way. They died as they lived – in service of the wild – leaving behind a painful reminder of the quiet heroes who risk everything for this planet.

In 2021, Sanctuary honoured him with the Young Naturalist Award in recognition of his unwavering commitment to wildlife. Resilient, resourceful, and deeply rooted in his landscape, Radheshyam embodied the spirit of grassroots conservation. His conservation leadership potential was unmistakable, and he became a part of Sanctuary’s growing network of on-ground defenders as a Mud on Boots Project Leader.

_C-1300_1749027521.jpg)

Photo: Sanctuary Photolibrary.

Everyone who knew Radhe knew he was selfless to the core, forever ready to jump into action if an animal or community member needed help. Radhe’s love for wildlife bloomed early. Born in Dholiya, a village near Pokharan in Rajasthan, he spent his teenage years racing across the desert to tend to injured wildlife. To gain firsthand experience in wildlife treatment, Radhe went to Jodhpur to assist at an animal rescue ward. It was there that he learnt about the plight of the critically endangered Godawan and helped build an extensive grassroots network of wildlife volunteers, and an anti-poaching system in Jaisalmer. For the years that followed, protecting the Godawan became Radhe’s life’s mission in his own unconventional ways.

Once, to draw authorities’ attention to a Godawan killed by an overhead power line collision, he climbed partway up a high-tension pole and refused to come down until an FIR was filed. In 2019, when a massive insecticide spray programme was planned to combat a locust invasion, Radhe alerted Dr. Sumit Dookia, his mentor, after observing the Godawan feeding on the locusts. This led to them launching a media campaign and submitting a memorandum, leading to a policy change within 24 hours. His swiftness halted spraying in key habitats, allowing the birds to enjoy the buffet safely. Some even laid a rare second clutch of eggs the following year. In response to the Thar’s brutal summer this year, he had created over a hundred watering holes across the Pokharan region. He drove over 10 km. in the middle of the night to refill a dry trough. “If we wait till morning, they won’t survive the night in this heat,” he said.

Radhe was also a self-taught photographer with an uncanny eye for birds. He documented 15 species that had never been recorded in Jaisalmer, using his images to inform research and advocate for nature-based tourism.

When asked how he manages to accomplish so much, he let out a long sigh, pointed to a chair, and said, “If this chair needs to be moved, a committee will be formed to decide how and when to move it. Years will go by. I, on the other hand, just move the chair and move on to the next task.”

Two weeks before his accident, Radhe had shared a dream with filmmaker Nirmal Verma: to turn the sacred Oran behind his farmhouse into a refuge for rescued wildlife. “All wild animals must be released into the wild. They don’t deserve cages. I’ll build the rescue centre slowly, step by step. Something that would inspire pride and stewardship across the village. This is a long fight...”

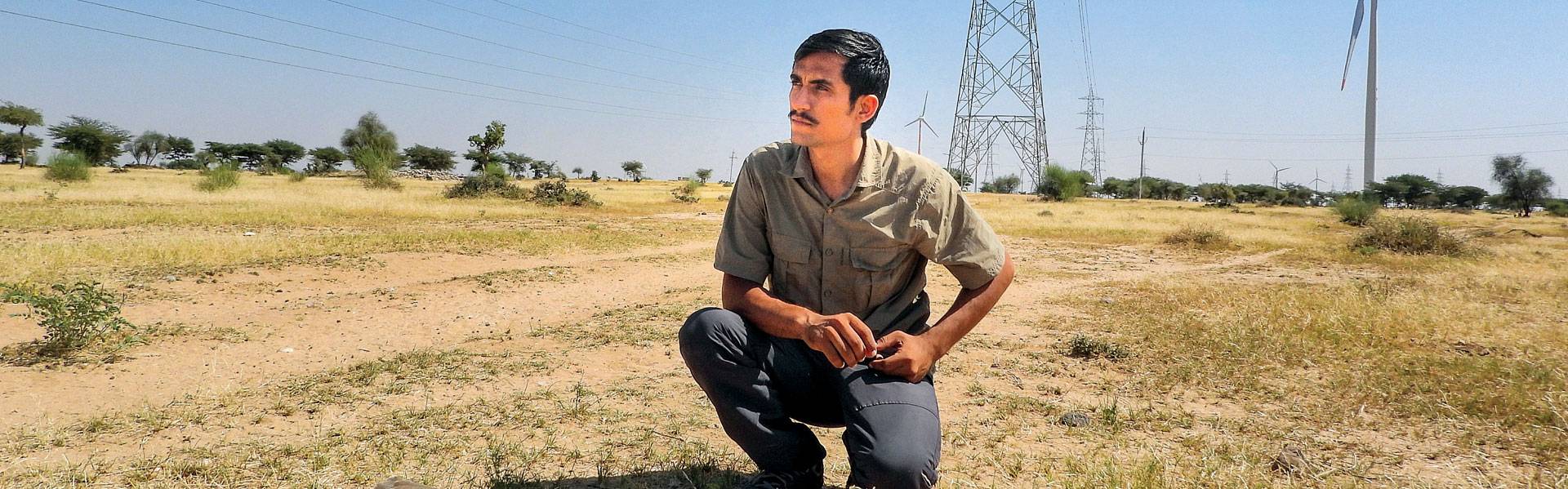

Radheshyam Pemani Bishnoi was lovingly called Radhe by everyone who knew him. His heart, mind and soul were dedicated to rescuing wild animals and the conservation of the Great Indian Bustard. He dreamt of building a rescue centre of his own over the years, a dream cut short by his tragic, untimely death. Photo: Sanctuary Photolibrary.

He had so much more to give. At 28, he was just getting started.

On being asked what would happen if the GIB went extinct, Radhe quietly said, “I don’t know…because it won’t.” And when we asked the others, they said, “We don’t know, because Radhe won’t let it go extinct.”

Radhe is survived by his wife and mother, who used to help him nurture and raise the orphaned wild animals he would bring home, his father, brother, and two young children, who would ask him every night if he “caught” a Godawan (in his camera). They will grow up hearing not just what an incredible wildlife hero their father was, but also how deeply he was loved.

Radhe brought together different communities, and his friends are determined to continue his legacy. “Our team may be broken, but we will fulfil the dreams we envisioned together,” said Sharvan Patel, one of Radhe’s close friends in the Thar. Together, they had set out to put the desert’s forgotten wildlife back on the map. Now, they all walk on for him.

Fly free, dear Godawan Man of India. The bustards soar higher in your honour.

_C-1300_1749027521.jpg)