The Third Pole

First published in Sanctuary Asia,

Vol. 45

No. 8,

August 2025

By Munib Khanyari

The Third Pole, which refers to the Himalaya and surrounding high mountain regions, is the world’s third-largest repository of ice and snow after the Arctic and Antarctic. It is a vital water source for over 1.9 billion people across Asia. Climate change poses severe threats to this fragile ecosystem. Glacier melt, rising temperatures, and altered weather patterns are endangering biodiversity, disrupting livelihoods, and increasing the risk of floods and landslides. As habitats struggle to cope with shifting conditions and floral and faunal species face extinction, local communities face a gamut of challenges as they bear the brunt of these environmental changes. Sanctuary Asia reached out to credible voices to understand these challenges and to highlight the need for quick collective action in the face of the faster-than-expected climate and ecological threats that have begun to take a vicious toll on lives and property.

The Melting Roof Of Asia

“I had to feed them dried maggi [instant noodles]; even though we had barely anything to eat, even that wasn’t enough…,” I heard a helpless Ache Llamo, a Changpa woman, say. We walked, in silence, seeing over 150 corpses of changluks and changras (sheep and goats from the Changthang plateau) laying silently. The Tongon herder camp, deep inside the remote Tegazong plateau, nearly an eight hour drive and then a horseback ride away from Leh, had just witnessed a winter like never before. Record-low winter temperatures along with freezing yet snowless winds, preceded by an unusually hot and dry summer, had made the already low productivity pastures of this high elevation plateau, even sparser in their offerings. The unseasonal and intense snowfall in late autumn, as the herds were migrating from the banks of Tsomoriri to their winter grounds in Tegazong, had already weakened the livestock.

Being in Tegazong is like taking a step back in time, no roads, no electricity, no phone connections. Each morsel needs rationing. Climate change here is not just a modelled prediction, but a lived, yet highly unpredictable and unforgiving reality for those that call it home.

The high-altitude marshes along the Hanle river (facing page), in Changthang, Ladakh, teem with life including mammals such as the Tibetan gazelle Procapra picticaudata and Pallas’s cat Otocolobus manul, to resident and migratory birds such as the Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis. Photo: Saurabh Sawant/Sanctuary Photolibrary.

Echoes From Tegazong

The Tegazong plateau forms a small portion of what is termed as the ‘Third Pole’ – the Tibetan plateau and its surrounding mountain ranges – which sustain the largest ice mass outside the North and South geographic poles. This region covers roughly five million square kilometres (just under twice the size of India), with an average elevation of more than 4,000 m. including over 100,000 sq. km. of glaciers. It is the most sensitive and readily visible indicator of climate change.

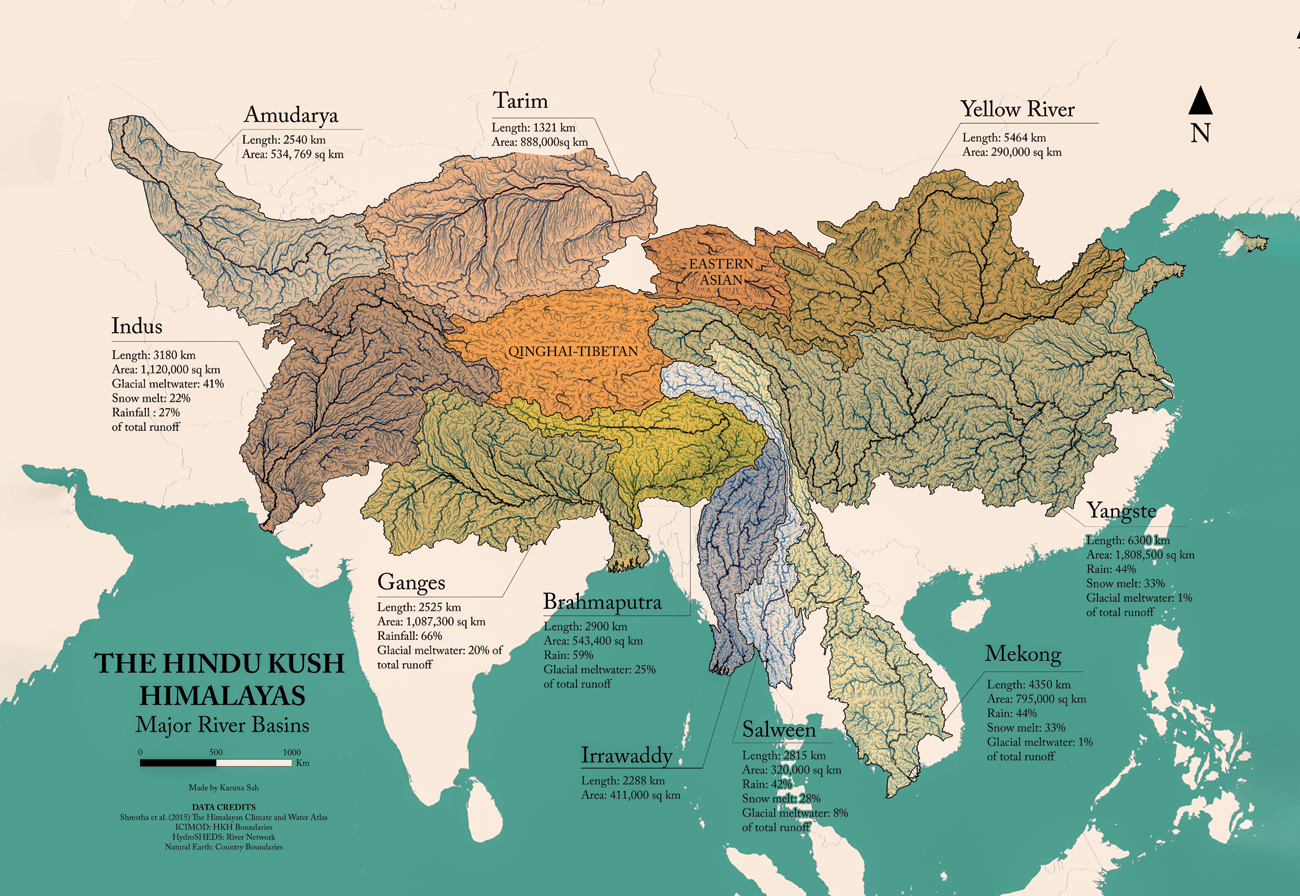

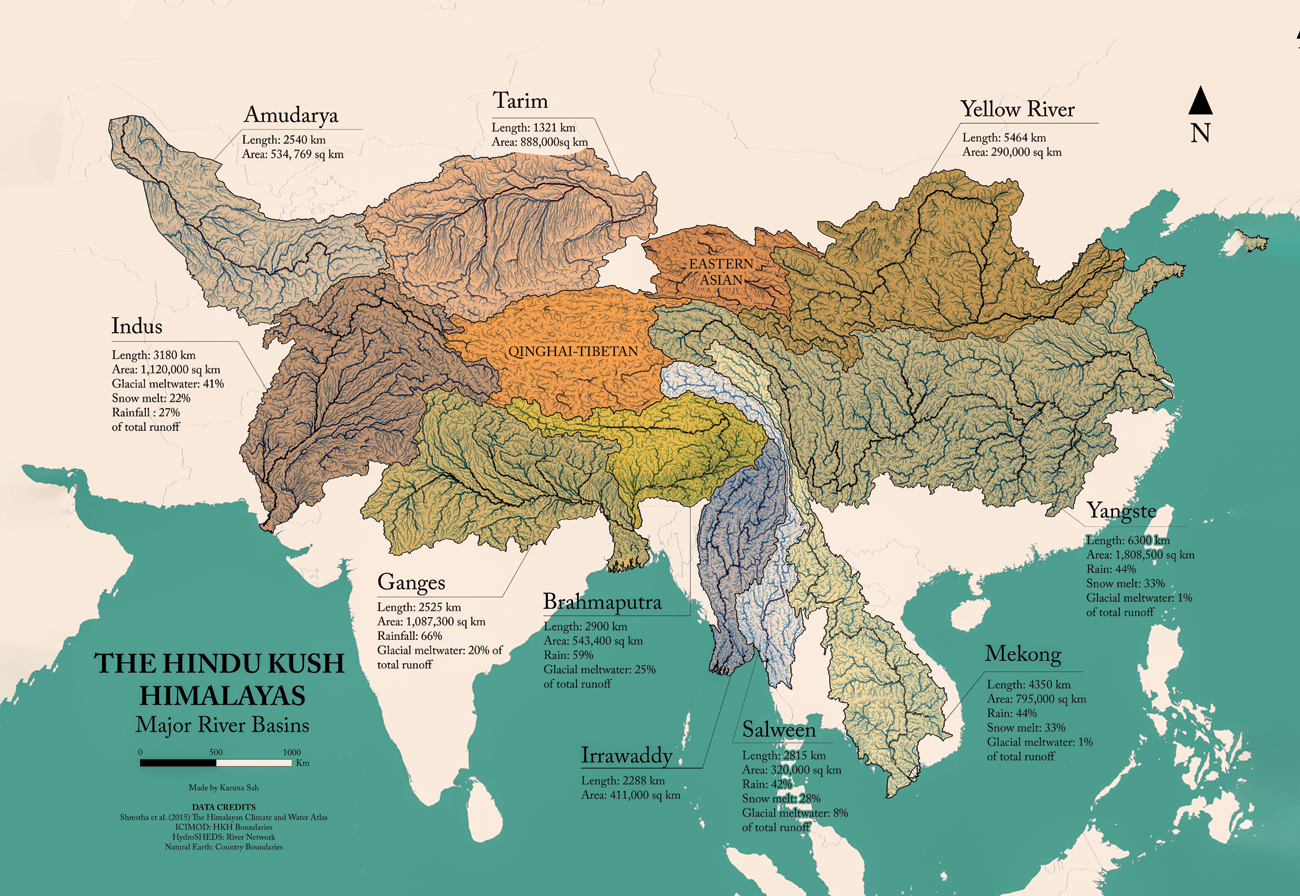

Given the high concentration of glaciers and peaks, the region gives rise to mighty rivers such as the Senge/Tsangpo/Indus, Ganges, Panj, Amu Darya, Drichu/Yangtze, Machu/Yellow, Zachu/Mekong, Gyalmo Ngulchu/Salween, and Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra. These rivers support life in some of the world’s most populous countries, such as Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and China. That’s directly or indirectly, almost 40 per cent of the world’s population. Fittingly, the Third Pole is also referred to as the Water Tower of Asia.

The large volume of ice and water here helps regulate the weather in the region, reflecting the sunlight and driving the Southwest monsoon, and preventing the dry, cold winds from Central Asia from entering the subcontinent. Besides, the Third Pole is home to an astounding variety of biodiversity. For instance, the Indian trans-Himalaya alone are said to be home to around 1,500 species of flowering plants. It is also home to the majestic ‘mountain monarchs’, the wild sheep and goats with males sporting impressive head gear. This includes the largest sheep in the world – the argali, and the largest goat in the world – the markhor, both of which have horns that can reach up to 180 cm. with the former’s curving around and the latter’s twirling towards the sky.

The Third Pole is also home to remarkable cultural diversity, including Tibetan Buddhists, Ladakhi agro-pastoralists, Sherpa mountaineers, and Mongolian nomads, each with distinct languages, livelihoods, and spiritual traditions shaped by high-altitude landscapes. From yak-herding rituals in Bhutan to salt caravans in western Tibet, these cultures reflect deep, place-based knowledge of survival in some of the world’s harshest environments. Glaciers such as the Gangotri and Yamunotri hold deep cultural, religious and spiritual significance for many people as well.

The Changpa, a nomadic pastoralist community of Tibetan origin in Ladakh, have long adapted to the harsh Himalayan climate and terrain. Many depend on rearing Pashmina goats, migrating with their herds through increasingly unpredictable seasonal shifts brought on by climate change. Photo: Munib Khanyari.

Nevertheless, like the precarious levels of oxygen in the air across the heights of the Third Pole, this region faces precarious consequences on account of climate change. Annually across the globe, on average about 273 billion tonnes of ice melts, which is enough to sustain the world’s water consumption for 30 years. Contributing to this, are some of the fastest melting glaciers in the Third Pole, with about 82 per cent glaciers in the Tibetan plateau showing signs of retreat; the region is also losing about 10 per cent of its permafrost. Much of this is attributed to black soot from pollution from the lowland area that travels higher up with the winds and settles on ice, and speeds up the melting process. Meltwater lakes are expanding rapidly, increasing the risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) that threaten communities downstream.

This accelerated climate change has multiple, often hard to understand, impacts on biodiversity. There is now increasing evidence of upwards shift of flora such as Abies spectabilis and Betula utilis expanding upslope owing to warming, altering regeneration patterns and stand structure in alpine zones. These often layered impacts include outcompeting high altitude specialist species, shrinking of alpine meadows – critical habitats for livestock and also high altitude wildlife, while also being culturally important – and disruption of pollinator networks, to state a few examples. There are also considerations that shifting treelines can alter species interactions. For instance, this can lead to severe competition between common leopards and snow leopards, which could be detrimental to the latter given its smaller body size and more specific habitat and diet requirements.

Erratic and unpredictable changes in climate also have devastating impacts on local livelihoods. Changing weather patterns are making migration timings for pastoral communities a challenge. From shrinking grazing areas on account of lack of summer rain and winter snows for the Changpas in Ladakh, to erratic late spring snowfall blocking Bakerwal migratory routes in the heights of Jammu and Kashmir, mobile pastoralists across the region are often negatively impacted by these climate changes. Farmers, especially in the mountains of Nepal and Bhutan, are facing unpredictable rainfall and shorter growing seasons, which threatens staple crops such as buckwheat and barley. Many, fearing GLOFs, have migrated away from high-elevation villages to lower valleys. These changes not just undermine economic security but also erode cultural practices tied to the land.

The Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) landscape, which harbours about 82 per cent of glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau, is rapidly changing, with the glaciers and ice fields of HKH showing worrying signs of retreat. The Randolph Glacier Inventory closely monitors these changes. Photo: Karuna Mira Sah.

Community Participation Paradigms

Clearly, the Third Pole is a melting pot of biological and cultural diversity, a source of life even for those who may never see the heights of its peaks, or cross geopolitical frontiers. Yet, the Third Pole is imperiled by climate uncertainty and political paralysis. While the situation may seem dire, it is important to introspect and do what can be done. It is here that we need to learn from people like Ache Llamo, the local people, for whom the Third Pole, to which they are well adapted, has been home for millenia, albeit in changing ways and forms. We need to work with these communities by adapting to their paradigm of participation, both for knowledge generation and on-ground action. This might involve looking back in time to hone in on contextually relevant solutions such as reviving locally sourced barley as a source of nutritious, organic and cost-effective winter fodder for livestock in Changthang. This was the order of the day just a few decades ago and is far better than relying on feed from the plains of Punjab that does not suit high-altitude livestock, has a huge ecological footprint, and costs too much.

Simultaneously, we will need to work towards paradigms of engagement by returning power and agency back to the communities at the frontline of the climate assault on the Third Pole. This will need a more convivial conservation approach to human-nature relationships, including recognising herding as a valued profession and providing salaries to pastoralists across the region. Such measures would not only honour the immense skill and labour involved in pastoralism but also help safeguard traditional livelihoods that are being displaced by poorly conceived development projects.

Such funding can be obtained by diverting misplaced subsidies provided to a slew of companies involved in mining, green energy projects, and other infrastructural projects that treat the Third Pole as a personalised geography to be commoditised. Such shifts need trust and respect-based collaborations with local and grassroots stakeholders. Crucially, these need to be long-term projects focused on ecological realities, not merely on economic imperatives.

We need proven, climate smart innovations such as the ‘Automated Ice Stupas’ that enhanced water availability for irrigation by 30 per cent, and increased agricultural productivity and strengthened local food security across the Ladakh and India’s Hindu Kush Himalayan regions, some of the harshest environments in the world.

For centuries, the countries that form the Third Pole were interconnected through trade and tradition, from the Silk Route to the Salt Route. Leveraging this symbolic connection, we need greater transboundary initiatives. The Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Programme (GSLEP) is one such effort, where 12 Central and South Asian countries are collaboratively addressing high-mountain development issues using the conservation of the charismatic and endangered snow leopard as a flagship. The stakes are high and the time is now. We don’t need more alarm bells, we need collective action for our Third Pole.

A Call To Action

Karishma Ahmed of the Balipara Foundation highlighted a multipronged approach in ‘The Himalayan’, a publication of the Eastern Himalayan Naturenomics Forum. She wrote: “The Third Pole and the wider Eastern Himalayan region are facing escalating threats from climate change, with projections indicating profound impacts on both ecosystems and local communities by mid-century and beyond. To mitigate these challenges and prevent irreversible damage, it is crucial to adopt a comprehensive strategy that combines strong policy measures with immediate, on-the-ground actions.”

Ahmed suggests that reducing the Himalayan region’s climate vulnerabilities requires a blend of global mitigation and local adaptation strategies. At the global level, reducing fossil fuel consumption and transitioning rapidly to renewable energy such as appropriate hydropower, solar, and wind can help communities to cope with the cascading impacts of climate in the Himalaya. Promoting energy-efficient technologies, electrified public transportation and policy incentives including subsidies for clean energy will help with mitigation and adaptation.

The people of The Third Pole were not responsible for the climate crisis that has the world in its grip. But they are among the worst affected victims. Ahmed stresses that we need to put people first by investing in early warning systems for floods, landslides, and GLOFs that are likely to become more frequent and deadly in the days ahead. This necessarily involves improved monitoring, forecasting and budgetary support. Community-level disaster preparedness programmes, climate risk mapping, and public awareness campaigns can help build local resilience. Educational initiatives should encourage sustainable practices and help communities reduce their carbon footprint.

This snow leopard, the ‘grey ghost of the mountains’, was captured on a camera trap by the Jammu and Kashmir Wildlife Department and the Nature Conservation Foundation. Like the tiger in forests, this highly endangered high-altitude cat is a flagship species of the Third Pole. Photo: JWKD and NCF.

Effective adaptation efforts involve focussing on climate-resilient agriculture, sustainable land use, and small watershed management strategies. All would involve nature-based solutions such as forest and wetland conservation that offer long-term resilience against floods and droughts. These must be supplemented by government policies that normalise climate-resilient infrastructure, updated building codes and mandated environmental assessments. Equally crucial, targeted insurance schemes and climate finance designed for vulnerable communities, which will bear the brunt of recurring extreme weather events long into the future, must be recognised as a right, not a privilege.

By showing that local communities are our focus, we will not just benefit from their pre-adapted wisdom, but also design holistic, integrated approaches and development plans in the Third Pole ecosystem.

Munib Khanyari An interdisciplinary researcher at the interface of pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in the High Indian Himalaya, he focusses on participatory, inclusive forms of co-inquiry with local communities to co-design conservation interventions. He is a post-doctoral researcher at ICTA-UAB and programme manager at the NCF.

The Third Pole: Key Highlights

Water Tower of Asia

* Encompasses 10 major river basins.

* Covers over four million sq. km.

* Supports people in at least 10 countries.

Glacial and Snow Resources

* Largest glacial concentration outside the poles (~7,000 cubic km. of volume).

* Snowfall is declining; glacial mass loss is up by 65 per cent from 2000–2020.

* Permafrost remains poorly understood.

Precipitation

* Primary source of water (snow and rain).

* Diminishing snowfall impacts long-term water availability.

Groundwater Crisis in Ladakh

* Borewells in Leh increased from 10 (1997) to 2,659 (2020).

* Groundwater extraction rose about 26 per cent in the last decade.

* Tourism growth led to contamination via poorly constructed septic systems.

Glacial Lakes & GLOF Risks:

* GLOF events recorded in Kedarnath, Gya, South Lhonak, etc.

* Remote sensing-based monitoring exists (ISRO + NRSC), but early warning systems and mitigation efforts are minimal and underdeveloped.

Climate Adaptation via Ice Stupas

* Artificial glaciers help counter water stress in April–May before natural glacier melt begins.

* Critical for farming in Ladakh, where only one cropping season is possible.

* Villages such as Ursi depend on snow-fed catchments and face severe stress without ice stupas.

Biodiversity, Livelihoods & Migration Risks

* Flora and fauna threatened.

* Climate uncertainty is forcing communities to consider abandoning traditional farmland.

* Reliable water access via innovations like ice stupas is becoming essential to avoid displacement.

With inputs from Karuna Mira Sah, a Remote Sensing Analyst at Acres of Ice, Ladakh, India.

The Global Relevance Of The Tibetan Plateau As The Earth’s Third Pole

By Tempa Gyaltsen Zamlha

The Tibetan Plateau, covering an area of 2.5 million sq. km. and standing at an average elevation of more than 4,000 m. above sea level, is the world’s highest and largest plateau. On account of its high elevation, this vast plateau contains over 46,000 glaciers across 14 major mountain ranges, making it the largest reservoir of ice and accessible freshwater outside the Arctic and Antarctic. The Earth’s Third Pole plays a crucial role in climate stability and water security in Asia.

The Tibetan plateau, owing to its extreme elevation and vast area of about two per cent of the Earth’s landmass, is experiencing a temperature rise twice the global average – 0.3 to 0.40C per decade. Climate change has severely impacted this fragile ecosystem, which in turn exacerbates global climatic shifts. Rapid glacier melt and permafrost degradation have led to an increased frequency of floods, landslides, glacier slides, and forest fires since 2015. Additionally, changes on the plateau significantly influence the timing and intensity of the Indian and East Asian monsoons. Growing evidence links intensified European heatwaves to retreating Tibetan glaciers. Scientists have also observed that greater snow cover in Tibet is associated with warmer winters in Canada, indicating that the Plateau’s climate impact extends across Asia, Europe, and North America.

Tibet’s unique geographic and ecological role positions it at the centre of Asia’s water systems and global climate balance. Protecting Tibet is essential for both regional water security and global climate regulation.

Therefore, the global community must recognise the ecological significance of the Tibetan plateau and take action to prevent further environmental degradation. Riparian countries must collaborate to preserve the Plateau’s fragile environment and safeguard its shared water resources. Most importantly, the Chinese government must respect the wisdom and rights of the Tibetan people to live in harmony with their environment. Tibet’s fragile ecosystem should not be jeopardised by extensive resource extraction in its mountains or the excessive construction of dams on its rivers. j

Tempa Gyaltsen Zamlha is the Deputy Director, Tibet Policy Institute, Central Tibetan Administration. An environmental researcher since 2011, his focus has centred on the global ecological significance of the Tibetan Plateau and the environmental challenges facing Tibet today. He has represented Tibetan environmental concerns at several major UN climate summits.

Carbon Stocks

By Mayank Kohli

Globally, soils hold over twice as much carbon as the atmosphere and all living organisms combined. A significant share of this is found in cold regions like the Hindu Kush Himalaya and the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, where microbial breakdown of plant and animal matter is slow. Over millennia, and aided by nutrient deposition by millions of livestock, this has led to vast carbon accumulation. In fact, the topsoil of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau alone contains an estimated 48 billion tonnes of carbon – nearly half the amount stored in the world’s tropical forests. Beneath this layer, the region’s permafrost, spanning approximately 1.5 million sq. km., holds more than twice that amount.

Today, these soils continue to sequester large amounts of carbon annually. But rising temperatures and rapid land-use changes threaten this capacity. As permafrost thaws and microbial activity increases, long-trapped carbon will begin to escape into the atmosphere, making climate change worse.

However, the most immediate threat may be mismanagement. To outsiders, the treeless landscapes of the Trans-Himalaya and Qinghai-Tibetan plateau often appear barren wastelands. This ‘Biome Awareness Disparity (BAD)’ – the bias toward forested biomes – has led to misguided afforestation efforts and lopsided development plans. Tree plantations, promoted for climate mitigation, are replacing native grasslands and pastures, harming both wildlife and local communities. Ironically, these projects often result in minimal carbon gains, while releasing ancient soil carbon when the ground is disturbed.

We must remember that reducing the value of this (or any) ecosystem to merely a carbon sink is short-sighted. Ecosystems are not just tools for offsetting humanity’s ever-increasing emissions – they are dynamic and complex living systems. We must move beyond a ‘carbon tunnel vision’ toward holistic regeneration, valuing the socio-ecological richness of the Third Pole. This vision will only be sustainable if it centres local participation, recognises community governance, and strengthens the stewardship of shared lands.

Mayank Kohli is an ecologist who has been studying grassland ecosystems in the trans-Himalaya for nearly 15 years. He is currently based at NCBS and supported by DST, India.

Geopolitics And Disasters

By Manshi Asher

Governments of countries falling in the Himalaya-Hindukush-Karakoram region, also referred to as the Third Pole, given its climatic and topographic features, see this landscape as a strategic frontier. In the post-colonial period, with the solidification of nation state boundaries and more so in the last two to three decades, the region has seen an intensification of tension and resultantly greater securitisation. Framing the Himalaya solely as a ‘geopolitical frontier’ invisibilises its ethnic, socio-cultural, ecological diversities and lived, complex histories as we view the region only through the lenses marred by territorial anxieties. Pressures of the global market combined with this strategic diplomacy are today driving the massive infrastructure push from all sides, erasing possibilities of plural, transboundary relationships that prioritise climate and socio-ecological justice rooted in regional cooperation and democratic governance.

On the one hand, climate change is accelerating glacier melt, altering rainfall patterns and intensifying slow onset and extreme events both, and on the other, extractive agendas from mega-dams to commercial tourism are exacerbating topographical vulnerabilities. Together these are reshaping not only the physical landscape but also the politics of access and control impacting the local societies and livelihoods in unprecedented ways.

Transboundary river governance, too, remains fractured in this contentious scenario. Though there is a growing need for regional cooperation grounded in ecological ethics and riparian justice, rivers continue to be seen as tools of territorial power with a focus on commodification through large dam building. Whereas people’s collectives, researchers and environmentalists from South Asia have been calling for salvaging trans-boundary relations through protecting treaties and rejecting technocratic water regimes. Cooperative and community-driven, holistic river governance that centres equity, risk reduction and the rights of smallholders, fisherfolk, and women has been a long standing demand from civil society initiatives.

In Ladakh, demands for Sixth Schedule status and statehood reflect resistance to centralised control over lands and resources. Indigenous communities there are demanding constitutional recognition to govern

trans-Himalayan lands currently threatened by tourism, solar parks, and rapid infrastructure expansion.

India’s disaster governance remains reactive, technocratic and dismissive of the ground realities in mountain states. While climate response has centred scientific knowledge production under missions like NMSHE, this climate response has privileged government-led scientists and scientific institutions with extensive resources. The studies conducted under this are centered on biophysical models over interdisciplinary and locally rooted research. This framing reduces climate risk to natural variables, ignoring structural drivers of vulnerability – dispossession, land use change, caste and gender exclusions and governance failures. Indigenous knowledge systems remain tokenised in climate mitigation and adaptation programmes – which continue to propose exclusionary conservation, market and engineering-based solutions such as river channelisation for floods or plantations for landslides.

Manshi Asher is a researcher-activist with two-and-a-half decades of experience of documentation, writing and campaigning for environmental justice. In 2009 she co-founded the Himdhara Collective, an autonomous environment group based in Himachal Pradesh. This excerpt is based on a recent essay, ‘A mission with a Himalayan vision’, published in the India International Quarterly, Vol.51, 3 & 4 (Winter 2024 Spring 2025).

Weaponised Rivers

By Parineeta Dandekar

Despite their myriad life-giving roles, the Indian Himalaya is primarily considered the hydro-powerhouse of the country by hydropower developers and governments alike. All of the Himalayan states in India, from Jammu and Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, are facing a hydropower onslaught. Down the years, some private dam developers have pulled out of projects, citing local protests. Even as the environment and communities are made into a bogey, most of the projects have been shelved by the developers themselves because of geological surprises, changing water yield, increasing disasters and climate change impacts which have been underplayed.

The starkest recent example is Sikkim’s Teesta III Hydroelectric Power Project, which was destroyed by a devastating glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) in October 2023, killing at least 55 people, also leading to the partial destruction of dams downstream. The GLOF event that led to the collapse was not a surprise – a number of scientists and communities had repeatedly spoken of the imminent threat of a GLOF from a lake upstream, but it was not taken into account, nor was accountability fixed. Now a new dam in the same place has already been approved by the Environment Ministry, based on the same old, flawed EIA. Glacial lakes across the Himalaya are rapidly expanding like the Ghepan Gath Lake in Lahaul, which has increased by 178 per cent in 30 years and poses severe threat to the downstream.

Himachal Pradesh is facing severe floods right now, and like in the Parvati river basin, people and places affected are close to hydropower facilities. In the Chenab basin in Jammu, dams are being built in cascades without looking at cumulative impacts or challenges specific to the region, which now include GLOFs to a large extent. During our recent field-based research, with Ohio State University, of Chenab, Jhelum and Beas basins from headwaters to exit points, we witnessed communities struggling against receding glaciers, changes in precipitation patterns, increasing climate disasters, drying groundwater sources and particularly melting permafrost. When a hydropower project with its dams, tunnels, muck and hydrological changes is added to this scenario, it becomes a recipe for disaster. For example, in the Chenab basin, Lindur village is subsiding because of permafrost melting, causing huge landslides and floods, and yet, two hydropower dams are planned just downstream.

Climate Change impacts have not been a part of the Indus Water Treaty and India has suspended the Treaty for now. However, the absence of a treaty should not be a reason for building more dams in the region, but to understand issues such as climate change, hydrological changes, and groundwater management, which were not a part of the treaty, but are profoundly affecting the basin. Through the ages, rivers of the Indus basin have been enduring symbols of love, creativity and sharing across the subcontinent. It will be a tragedy to look at them simply as weapons in a conflict. Rivers originating around the Third Pole also support non-human communities and unique biodiversity. The Indus in its headwaters is not only a source of water but a highway and a stopover for several migrating birds and animals.

The permafrost on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau stores more than twice the carbon found in the region’s topsoil, which alone holds nearly half the carbon stored in the world’s tropical forests. Photo: Mayank Kohli.

India’s large hydropower projects are counted as a contribution towards green energy, but green energy from hydropower, especially large hydropower, is a sham because of its unaddressed impacts. If hydro projects are alienating communities, dumping mud inside the river, submerging forests, increasing disasters and changing the hydrological regime downstream, should we call them green? Carbon is a limiting currency for the environment.

Local communities, apart from being the rightful stewards of the land, are also valuable and vigilant resource persons and partners in monitoring receding glaciers, glacial lakes, flooding patterns, groundwater changes, etc. However, their concerns and lived experiences do not receive a respectful place at discussions and hence, are not informing policy decisions or scientific studies to the extent that they can. On one hand, cutting edge scientific research of their environment does not reach the community, and on the other, valuable community insights do not reach real-time scientific studies. The Third Pole will gain hugely by bridging these gaps. Rivers originating in and around the Third Pole feed billions of people in South and South East Asia and yet headwaters of rivers such as the Indus, Sutlej and Salween are ridden with conflicts around hydropower. It is time the headwater regions and their human and non-human communities are perceived for what they are: precious, fragile, and powerful source regions on which billions depend for life, livelihood, and inspiration.

Parineeta Dandekar is the Associate Coordinator at South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP), a network working on issues related to rivers, communities and large-scale water infrastructure.

Beyond Global Forums: Why The Third Pole Demands Urgent Regional Action

By Shailendra Yashwant

Despite the existential importance of the Third Pole, it remains startlingly absent from focused action within global climate frameworks such as the UNFCCC. The slow grind of Climate COP summits underscores a stark reality: the Third Pole cannot wait for global consensus on urgent climate action.

Its survival demands immediate, robust regional cooperation. The complex, transboundary nature of its rivers flowing through China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bhutan, and beyond, renders fragmented national efforts insufficient. Coordinated governance is imperative for managing shared water resources, building disaster resilience, and implementing early warning systems as the ice retreats.

However, deep-seated political tensions and fractured institutions, such as the underperforming SAARC, have stifled collaboration. This paralysis is a luxury we can no longer afford. Overcoming these barriers is non-negotiable for safeguarding biodiversity, mountain livelihoods, and the freshwater lifelines of billions.

While the Climate COP30 at Belem, Brazil, later this year must find ways to prioritise the Third Pole in its deliberations, hope increasingly lies in emerging regional platforms. The Third Pole Climate Forum is pioneering practical cooperation through seasonal forecasts and vital scientific data sharing. Nepal’s Sagarmatha Sambaad provides a unique diplomatic stage, pushing for inclusive finance, cross-border research, and community-centered solutions. Technical bodies such as ICIMOD, UNESCAP, the Mountain Research Initiative, and the Global Cryosphere Watch offer indispensable research, support, and advocacy.

In Ladakh, demands for Sixth Schedule status and statehood reflect resistance to centralised control over land and resources. Indigenous communities are demanding constitutional recognition to govern trans-Himalayan lands currently threatened by tourism, solar parks, and infrastructure expansion. Photo: Rigzen Dorjay.

These mechanisms, alongside civil society efforts to revitalise SAARC’s environmental mandate, provide the essential framework. Together, they can unlock investment, harmonise policies, and, crucially, build trust through shared data and coordinated action. The enduring, albeit recently tested, success of the Indus Waters Treaty proves such cooperation is possible, even amidst political friction.

Protecting the Third Pole, Asia’s vital water tower requires a fundamental shift. The path forward lies in empowering regional collaboration, leveraging science as diplomacy, and directing finance towards shared solutions. The cost of inaction is simply unthinkable.

An independent photographer, writer and journalist, Shailendra Yashwant is currently a senior advisor to the Climate Action Network South Asia, and steering committee member of the Pesticide Action Network India.